Are Singles Less Happy?

This is a couple I met while hiking near Zhangjiajie, China.

Chinese friends I've shared this photo with sometimes say bái tóu xié lǎo ("bye toe she-yeah laow"). The literal meaning is "white hair together old".

Ordinarily, you say this to engaged couples or newlyweds. In essence you're wishing them a long and happy marriage. But the phrase, by itself, is grammatically flexible. Applied to the photo, it could mean that the two macaques have already been happily coupled for many years.

Either way, the underlying assumption is that people (and monkeys) are happiest when they partner up, stay partnered, and grow old together. This is not a uniquely Chinese idea. People in many countries, including the U.S., assume that marriage, or at least committed partnership, tends to be a happier arrangement than living single. Carried to the extreme, this assumption manifests as "singlism", a term coined by researcher Bella DePaulo to describe the many kinds of prejudice and discrimination that single adults experience.

In this newsletter I want to discuss a new study that questions the received wisdom about being coupled. Although prior research suggests that married people are happier than singles, on average, the new study calls out the limitations of using means (i.e., mathematical averages) to compare groups. Although the researchers end up relying on means, the way they use them is more sophisticated than usual, and thus, in my view, their findings are more credible.

This is an important topic, because the number of unpartnered Americans continues to increase and has now reached about 40%. Are all these single people living less happy lives than their coupled peers?

New study

The new study, published last Friday in the Journal of Personal and Social Relationships, was led by Dr. Lisa Walsh at UCLA.

Dr. Walsh and colleagues point out that in many studies, "singles are treated as a comparison group whose primary purpose is to serve as the unhappy contrast to their coupled peers."

Groups can be compared in lots of ways. Walsh and colleagues are concerned that most studies rely on "mean comparisons of single versus coupled people to conclude that singles (on average) are less happy than couples (on average)."

Before getting to Walsh and colleagues' approach, I want to discuss one reason why mean comparisons can be problematic.

Means and variability

There's an old joke about a statistician who drowned because he tried to wade across a river that's 3 feet deep, on average.

You don't have to be a statistician to get this joke. Most people expect variability around mean values. Even people who never, ever use phrases like "variability around mean values" expect it. We all understand that an average depth of 3 feet is consistent with the river being, say, 8 feet deep in places.

This joke illustrates one of the perils of relying too heavily on means: A mean tells you nothing about the extent of variability within a distribution.

In spite of this limitation (and others), means have become widely used in research since the early 20th century, in part because they're informative and easy to work with – and, in some cases, because they're clearly the best tool for comparing groups.

The fact that a scientific practice is normative doesn't guarantee that it's universally appropriate. Being single (or coupled) is a source of joy for some folks and constant misery for others, but many other variables influence our happiness. Simply comparing the average single to the average coupled person may conceal the influence of other variables, just as describing a river as 3 feet deep on average may conceal the fact that it's dangerously deep in places. I say more about this below and in the Appendix. For now, back to the new study...

Sampling

For this study, 2,000 American adults (18 to 65+) completed a 20-minute online survey.

The sample was intentionally chosen to be representative of American adults with respect to age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and annual income. In short, I would call it a strong sample.

Survey

You may be wondering: How did they measure happiness?

There's a ton of happiness research. There's even a respectable, peer-reviewed journal called the Journal of Happiness Studies. Still, one could feel cranky about the prospect of measuring it, as I once did. (How could happiness be measured on a survey? What is happiness anyway?)

I believe that one of the keys to happiness is to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If good work can be done but perfection is unattainable, then good will be good enough.

I don't always follow my own advice, but in this newsletter I will. I think that Walsh and colleagues did a very, very good job of measuring happiness.

Walsh and colleagues assumed that a person's degree of happiness reflects how satisfied they are with their lives overall, how satisfied they are in specific domains such as health and social support, and how much they experience various positive and negative emotions.

Their survey data consisted of 13 items that tapped into overall and domain satisfaction – but not emotional experiences, because, as they put it, "emotions tend to be relatively transient in day-to-day life."

I think this makes sense, even if leaving out emotional experiences seems like a less-than-perfect approach. Someone who feels sad or angry most of the time must surely be less happy than someone who experiences much joy and relatively few negative emotions. Still, over time, people experience a wide range of emotional states. If you don't, you're insane. I don't mean to be glib by saying that. One thing that contemporary views of mental illness, as embodied in the DSM-5-TR, have in common with traditional views of insanity dating back more than a thousand years, is that a person will be considered insane, or mentally ill, if they only experience one emotion all of the time. (Which emotion? Any of them.)

Along with measuring happiness, the survey also tapped into the following predictors of happiness drawn from prior work on the topic.

Interpersonal predictors:

–friendship satisfaction

–closest friend intimacy

–family satisfaction

Intrapersonal predictors:

–self-esteem

–perceived stress

–physical health

"Interpersonal predictors" concern relationships with others, while "intrapersonal predictors" concern oneself. (Romantic relationship satisfaction was also considered for the couples.)

This strikes me as a sensible list. Even if you don't consider it a perfect set of predictors, I think you'd agree that they tell us something of importance about happiness, or life satisfaction, or whatever you wish to call it.

Each of the predictors was measured by a set of items rated by participants. For instance, perceived stress was measured by four items, such as “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”, rated on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often).

Evaluation of survey

How often are survey questions perfect? On a scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (almost always), my answer would be a 1. It's just not possible to choose survey items that are completely unambiguous and interpreted correctly by 100% of respondents. For instance, a person living a relatively stress-free life may not feel they could control, or even want to control, the important things they experienced last month.

Still, I think that most questions on this survey were as clear as they could be. If there's a little noise in the data because a particular question didn't quite fit a particular person, it doesn't follow that this occurred frequently, or that it differentially affected single vs. coupled people.

Another source of noise in survey data occurs when participants become bored or inattentive and start answering carelessly, or choosing answers at random. To prevent this problem, the survey contained five engagement checks. In response to a query, Dr. Walsh emailed me an example of one such check, wherein respondents are simply asked to "please select 'somewhat agree' here." Survey responses from people who failed one or more engagement checks were excluded from data analysis.

On the whole, I found this to be a strong survey.

Findings

The main analyses accomplished two things:

(i) Identification of distinct profiles, or types of people.

(ii) Comparisons of mean happiness scores for each type of person.

Here are the key findings:

The terms "favorable", "mixed", and "unfavorable" are informal ways of describing scores on the predictor variables. (If you're a stats person, check out the study itself on the use of Latent Profile Analysis, and for details on how these labels were derived from Cohen's effect size thresholds.)

For instance, among singles, Type 1 people scored relatively high on each of the interpersonal and intrapersonal predictors listed earlier. Roughly, these people are happy with their friends and family, and they feel pretty good about themselves too.

Type 2 singles also feel pretty good about themselves, but their interpersonal experiences are "mixed" in the sense that their family connections are solid but something is lacking in relationships with friends.

Type 3 singles, in contrast, are happy about their connections with family and friends, but they're not doing so well intrapersonally. They're a bit low in self-esteem, they're a little stressed out, and their health isn't quite as good as they'd like.

You get the idea. "Favorable" means that things are going relatively well with respect to all predictors; "unfavorable" means relatively poor functioning for all. "Mixed" means different things depending on type. For instance, Type 5 singles are described as mixed, interpersonally speaking, because they have solid friendships, but their family relationships are unsatisfying. Coupled people representing Type 2 are mixed, intrapersonally speaking, in the sense that their health is fine but they experience low self-esteem and high stress.

Finally, the far right column of each table shows the mean happiness scores. (The highest possible score would be 123.)

The key finding

Here's the most important thing to notice about the data: Within each table, the happiness means range widely across types. When types that could be directly compared were compared (e.g., single Type 1 vs. coupled Type 1), no significant differences between singles and couples emerged.

In other words, the happiest singles tend to be as happy as the happiest coupled people. The unhappiest singles tend to be as unhappy as the unhappiest people in relationships. Same for most points in between, though the results get more nuanced when considering less extreme types.

In short, Walsh and colleagues found that with respect to happiness, it doesn't make much sense to divide the world into single vs. coupled and then compare the two groups. As the researchers put it, "happiness and unhappiness looks rather similar for both single and coupled people."

Another way to say this is that even though being single or coupled can influence peoples' happiness, other variables, taken together, tend to have a stronger influence.

Of course there are exceptions. Someone trapped in an unhappy marriage may feel desperately unhappy, regardless of other good things in their life. Sometimes one close, fulfilling relationship can make an otherwise unpleasant life feel joyful and rich.

The new study findings don't deny the existence of exceptions. Rather, the data show that overall, merely being coupled or single doesn't tend to determine how happy people are.

What an encouraging and useful conclusion! The data tell us that whether you're a therapist, a young adult pondering your current or future relationship status, an older parent concerned about the well-being of your adult child, or a reader of last week's Atlantic article claiming that married people are happier, period, it's important to be open to all possible relationship statuses. Yes, people still experience cultural pressure to be coupled. There's pressure in some quarters to stay single too. But what makes people happiest will vary from person to person.

Some people really need to be married, or otherwise coupled. Others, like Bella DePaulo, have made the happy discovery that they're Single at Heart, as she puts it. Still others, like me, have found happiness on both sides of the fence. Most importantly, what makes a person happy is determined by many things. The new study reminds us that we shouldn't expect relationship status to automatically predict more or less happiness. That should be good news for the roughly 40% of single Americans – and for the 60% who are currently coupled.

Thanks for reading!

Appendix: Blueberry pie

In this appendix, I want to demonstrate that even when groups differ on average, it might not make sense to compare them. I'll use blueberry pie to illustrate the point, then explain the connection to Walsh and colleagues' study.

In short, this is an informal way of discussing some important statistical concepts that researchers sometimes overlook.

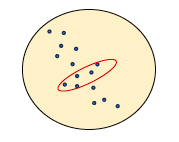

In the blueberry pie depicted below, the blueberries have been strewn in a diagonal path from upper left to lower right. (What a lazy baker!) You can also see that the left half of the pie contains more blueberries than the right half.

Imagine that the baker always bakes blueberry pies this way, and that you've been a loyal customer for many years. (The picture above depicts the inside of the pie, which you can't see before you cut a slice.)

Over a period of years, you would notice that you get more blueberries, on average, when you take a slice of pie from the left side as opposed to the right. (Assume the pan is marked in some way that left and right are consistently identified.) Naturally, you would conclude that the left halves of the pies contain more blueberries. However, that's a misguided conclusion if you care about how many blueberries you'll get whenever you cut yourself a slice.

If this is indeed what you care about, thinking of the pie in terms of left vs. right side will be minimally helpful. What you need to do is to suss out that diagonal pattern. To the extent that you can do this, your accuracy at predicting blueberry content will be much greater than it would be if you just took a random slice from one half.

In other words, if you care about how many blueberries you'll get per slice, you should stop thinking about left vs. right halves. It's an irrelevant distinction. What's important is the difference between that diagonal swath (lots of blueberries) and everything else (no blueberries).

Notice too that if you want lots of blueberries and you're willing to slice carefully, there's a smaller diagonal area that's also especially densely blueberried. (I've reproduced the pie below with that area circled.) Here again, the distinction between left and right halves would be meaningless, because the smaller diagonal extends into both halves. If you want a lot of blueberries, you need to either find that main diagonal from upper left to lower right, or that small diagonal area that I've circled.

This blueberry pie scenario is a crude analogy for Walsh and colleagues' statistical approach. Prior researchers compared one side of the pie (i.e., coupled people) to the other side (i.e., single people) and said look, we found more blueberries (i.e., happiness) on the coupled side. Dr. Walsh and colleagues said look, by dividing up the pie in other ways, we get a clearer sense of where the blueberries are. Regardless of which side of the pie you consider, there are more blueberries in some places than others. Some types of people, whether single or coupled, tend to be very happy. Some types of people, whether single or coupled, tend to be less happy. (The large diagonal swath represents Type 1 people. The small diagonal swath represents some other type. My pie is not meant to be a literal depiction of any particular type though.)

Walsh and colleagues didn't find substantially more blueberries on one side as opposed to the other. "Side" just isn't a very important variable. For instance, in the redrawn pie below, the darker the background, the greater the density of positive interpersonal and intrapersonal experiences. You can see now that it doesn't matter whether people are coupled (left half of pie) or singled (right half). Lots of positive inter- and intrapersonal experiences is where the blueberries are.