I think I disappoint my running watch.

Please, it whispers, I have so much to offer. Let me tell you your heart rate, your caloric output, your oxygen saturation, your V02 max, your....

Nah. Just pace and distance, please.

Maybe it's a reflection of my age, but I feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of personal health data at my fingertips (literally), thanks to fitness trackers, patient portals, DIY tests, etc. Health wearables now represent a $72.5 billion per year industry. Pharmacies like CVS sell more than two dozen types of home health test kits.

According to national news reports, a study published last week shows that a simple fitness test can even predict how long you'll live. The test can be done at home, in a few minutes, with no equipment.

As you'll see, the test doesn't predict longevity. The journalists got this one dead wrong (no pun intended). But the test is useful, and in a moment I will encourage you to try it.

A key distinction

The test I'll be describing relies on a simple distinction between aerobic and non-aerobic fitness.

Aerobic fitness refers to how efficiently oxygen is delivered to the muscles.

Non-aerobic fitness includes muscle strength, flexibility, balance, and body composition, and it predicts a variety of health outcomes, particularly later in life.

The sitting-rising test (SRT)

The sitting-rising test (SRT) is a simple measure of non-aerobic fitness.

I invite you to take this test, unless you have a specific joint or balance problem that makes falling likely.

Simply put, the SRT measures how much support you need to sit down on the floor and then get back up again.

It's not a timed test; your score is not based on how quickly you finish.

Here are the instructions:

“Without worrying about the speed of movement, try to sit and then to rise from the floor, using the minimum support that you believe is needed.”

In lab studies, additional instructions are given to folks who struggle, since the goal is to figure out how well a person can do at their best. For instance, a person might be told to cross one foot in front of the other. (This makes both sitting and rising easier for some people.)

Each part of the test (sitting and rising) is scored from 0 to 5. Thus, the maximum SRT score is a 10.

Scoring itself easy: For each part of the test, start with a 5, then deduct one point for each body part you use for support (hand, forearm, side of leg, or knee). Also, deduct half a point if your movements are very unsteady.

Remember to do the test barefoot. Take all the time you need. And, feel free to repeat each part of the test. Your best score is the one that counts.

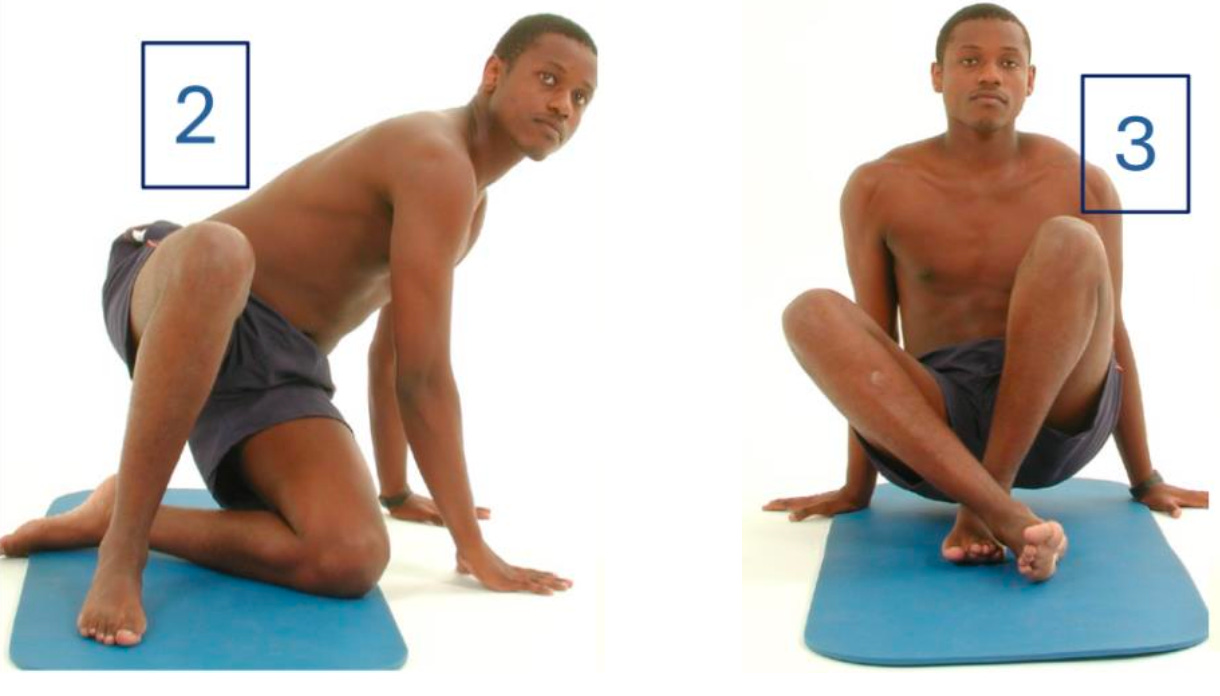

To illustrate the scoring, compare these photos of a man who's almost finished sitting down:

In the photo on the left, the man's sitting score would be a 2 out of 5 – he loses one point for the side of his leg and one point for each hand. In the photo on the right, his score would be a 3, as he only loses points for using his hands.

(No deductions for using the sides of your feet.)

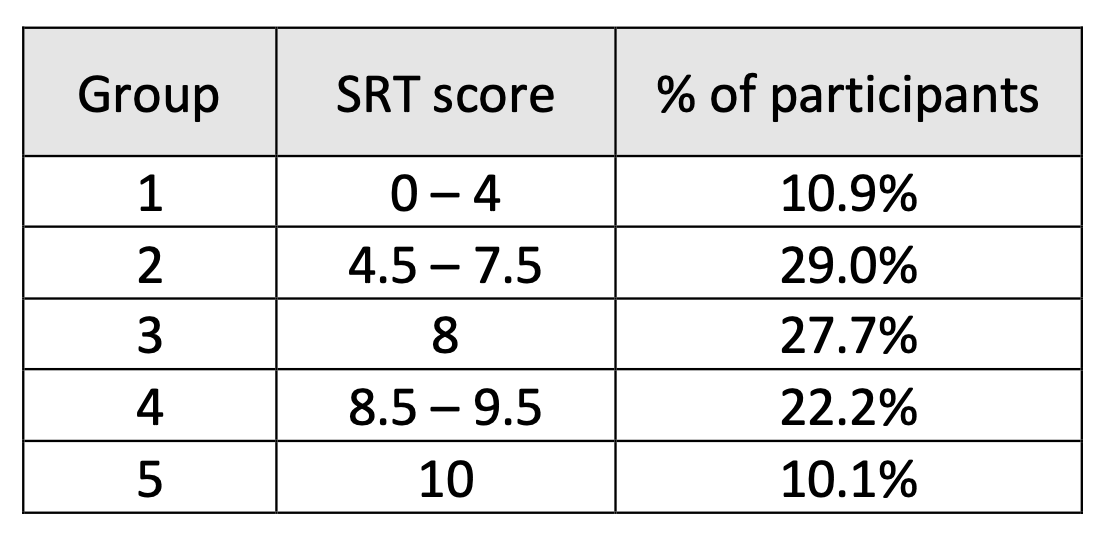

Have you done the test? Chances are, your score is less than 10 – only 10.1% of people in the new study got a perfect score – but, as you'll see, that's not necessarily a cause for concern.

The new study

Claudio Gil S. Araújo, the Brazilian researcher who created the sitting-rising test back in the late 1990s, is the lead author for the new study, published this June 18th in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

Araújo and an international team tracked 4,282 adults (ages 46 to 75) for a period of up to 26 years. The goal was to figure out the relationship between SRT score and mortality.

The researchers focused on deaths from natural causes. In most cases, this meant cardiovascular disease, cancer, or respiratory disease. Excluded were COVID-19 deaths, as well as those from external causes, such as traffic accidents.

Based on initial SRT scores, participants were divided into 5 groups:

665 participants died of natural causes during the followup period. After taking into account differences in age, sex, BMI, and health history, Araújo and colleagues found the expected association between group and mortality.

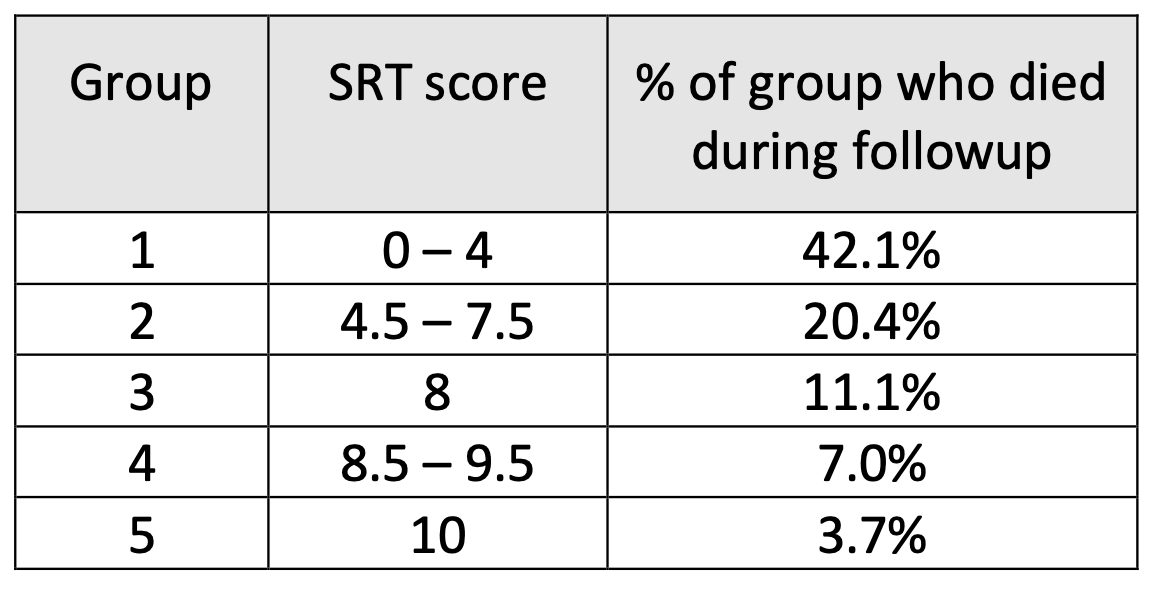

At first glance, the data look grim for anyone whose SRT score is less than 10. Here are the key figures:

Starting from the bottom of the table and working your way up, the percentage of deaths nearly doubles for each SRT group compared to one below it. A little scary, right?

Some reassurance

1. The differences between groups 3, 4, and 5 were not significant.

How could this be? The mortality rate for group 3 (11.1%) was three times higher than for group 5 (3.7%).

The simple answer is that compared to group 5, more people in groups 3 and 4 had health problems (cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and/or diabetes).

I can't tell you the exact rates, because the researchers don't provide them. But the point is this: Differences between groups 3, 4, and 5 in mortality rates are due in part to differences in health rather than non-aerobic fitness.

This is not to say that SRT scores are meaningless. Groups 1 and 2 did have significantly higher mortality rates than group 5, and there were other signs that higher SRT scores are desirable. Just don't expect the SRT to generate very concrete dose-response predictions.

So, what does the test actually tell us?

Consider again those national news reports:

Sorry, no.

The study does not predict how long a person will live. Rather, it tells us that the higher the SRT score, the greater a person's chances of survival over an extended period of time.

Let me put that concretely. About 15% of the study participants were no longer alive in 2024. The higher the SRT score, the greater the chances that a participant would be among the survivors.

This is very different from saying that SRT score tells us how long someone will live.

It's also reassuring, because it reminds us that the study only tells us about the chances of some outcome (surviving or not). Saying that A increases your chances of B doesn't mean that if A occurs, B automatically follows.

Think of it this way: A low SRT score may point to health problems that can shorten your life, but any one person's longevity is determined by many factors. Someone in group 1 who leads a healthy lifestyle may outlive someone in group 5 who's chronically stressed and relies heavily on alcohol to cope.

2. Smoking behavior wasn't measured.

The researchers had no data on smoking behavior. They mention this as a limitation of the study, though they don't explain why.

I think the reason is clear: Studies have shown that people who are obese and/or highly sedentary are also more likely to smoke.

If smokers who obtain low SRT scores owing to excess weight or lack of muscular strength don't live as long, the culprit may be the smoking rather than their non-aerobic fitness.

If this is the case, then low SRT scores may not be quite so bad for non-smokers (even though, all things equal, higher scores would be preferable).

3. SRT scores are malleable.

You can improve your SRT score by working on balance, muscle strength, and flexibility. (Helpful guidance can be found here.) These changes are good for you, and they might extend your life (though you wouldn't know by how much).

Is the SRT useful?

At first glance, the SRT seems redundant.

The researchers claim that low scores might result from obesity, balance issues, muscular weakness, and/or inflexibility.

If you struggle with excess weight, you and your doctor already know it. Tests already exist for grip strength, balance, flexibility etc. – in 2022, Araújo himself showed that standing on one leg (with the other thigh parallel to the ground) for 10 seconds predicts longer life.

The value of the SRT, Araújo notes, is that with a single test, all aspects of non-aerobic fitness can be easily measured. This makes the SRT useful for health care providers, as well as for folks interested in personal health data on capabilities that can be improved.

Final thoughts

I think it's worthwhile to reflect on your SRT performance – so long as you don't obsess about the score.

A low score may tell you something you're already aware of. If so, you're just quantifying an existing problem. You needn't be concerned that something else is wrong.

Moreover, a low score doesn't automatically translate into diminished longevity, as I mentioned earlier, while a high score might be misleading and create overconfidence.

For instance, I scored a 10 on the SRT, but I have a flexibility issue the test doesn't capture: Turning my head approximately 90 degrees is harder than it used to be.

This is problematic when I run, because I cover long distances, I live in a place where running on the street can't be completely avoided, and I'm hard of hearing. I often fail to notice vehicles behind me until they're passing.

Thus, in my case, the SRT fails to measure a risk factor for injury (or worse) that arises from an incompatibility between the bodies of runners and cars.

The moral of the story is that a test may tell you something, but it can't tell you everything. That's true for all sorts of tests, whether they measure intelligence, personality, achievement, or health. We live very quantified lives, and so we need to be thoughtful about the numbers.

Thanks for reading!

Fun article, fun test - kudos for bringing it to light!

I thought this was going to be a six minute walk test or a "cover a mile distance however you want as fast as you can" as the proxy, but the sitting and standing using feet only is a new one to me.

On running - as a long-time runner who has spent a lot of time in city traffic, have you considered running against traffic? It's my preferred method, because then there's full visibility on both sides, and if one side is asleep at the wheel (as is more often the case) it gives the other side the chance to proactively alter course before any truly close calls.

I'll do that for running, but not for cycling, because of the space taken in the respective modes - and the amount of close calls I get when cycling 'with' traffic from people in SUV's whipping by within an inch or so (as they stare at their phones) is easily 10x the close calls I ever get running against traffic.

I can do it and get a 10 but it’s not graceful and I’ll suggest if you try too hard it feels like a good way to hurt yourself.