Forest bathing.

When I hear the phrase, I think of the day I was hiking in Shenandoah, sans umbrella, and got caught in a downpour. That was quite a bath.

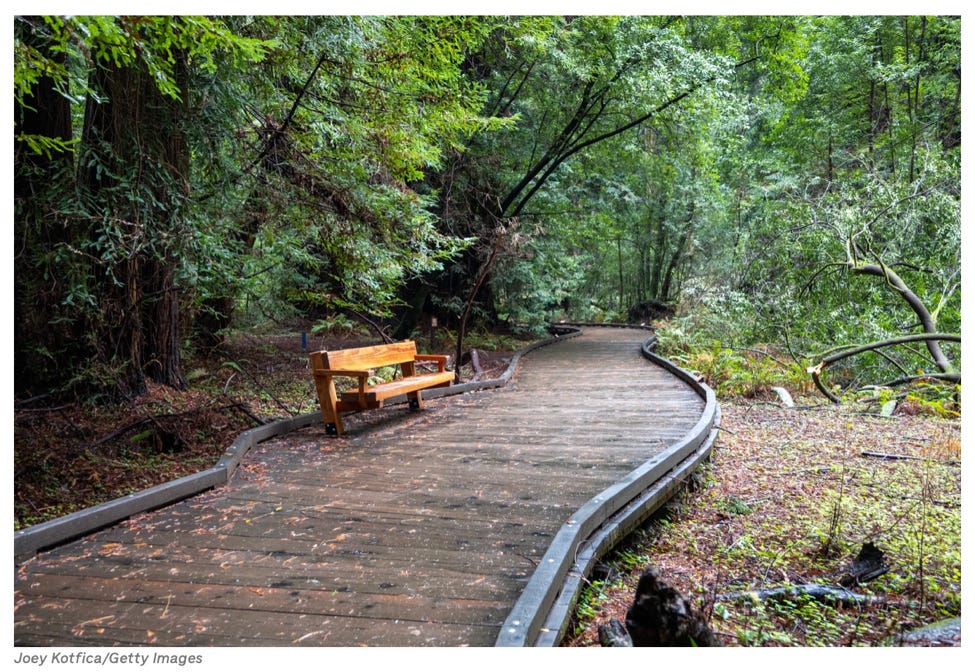

Practitioners have something more pleasant in mind: Spending time in the woods, relaxing, tuning in to nature.

Studies suggest that forest bathing reduces stress, strengthens the immune system, and improves cognition and mood. Can we trust the data? If we can, is there something special about trees? What about other natural settings? Is merely leaving the house enough? (An often-cited study found that Americans spend less than 10% of their time outdoors.)

In the first and last parts of this newsletter, I address these questions and offer some practical suggestions.

In between, I discuss a new study suggesting that even virtual reality (VR) simulations of a forest can lower stress levels.

I love trees. I write these newsletters in their presence. But I listen to science too, even if I dislike what it has to say. For instance, I found the premise of the new study disturbing. Why encourage people to lounge around the house wearing VR headsets, as opposed to experiencing actual forests?

Then I remembered cities like Phoenix, where wooded areas are inaccessible for people who lack time and transportation. For these folks, simulated forests might be better than nothing...

Simple origins

Some health fads stem from grifters trying to make a buck or, nowadays, social media influencers seeking attention.

Forest bathing has nobler origins. In 1982, the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries introduced shinrin-yoku ("forest bathing") as a way of alleviating stress created by rapid urbanization, as well as promoting conservation of forest land.

In short, the aim was to support both public and environmental health.

Commercialization

Since 1982, forest bathing has become increasingly monetized. You can enroll in online courses, become certified as a guide or forest therapist, et cetera.

There's considerable emphasis here on another kind of greenery (i.e., dollars) and, like the VR simulations, this also rubs me the wrong way.

Forest bathing is a process of immersing oneself in the sensory experiences of the woods. The guidelines are fairly simple. Don't bring your cell phone or your earbuds. Don't carve your initials into a tree. Just walk, or sit quietly, and connect. Who needs to pay to learn how to do this?

Some organizations sell techniques for "barefooting" and "digital detox", but look, once you get to the forest just take your shoes off, watch where you walk, and power down your phone. I can tell you that for free.

Most disturbing is Treeming.org, which sells a training package for individuals as well as a costlier one for becoming a certified forest bathing guide. The individual package is pitched to folks "who just wanna use forest bathing for themselves and NOT teach it to others", which seems to wanna coerce you into keeping secrets, or shame you into choosing the more expensive option.

These are separate packages, but as of today each one has received 4,853 ratings and averaged 4.91 out of 5 stars. Statistically, this can be interpreted in many ways, none of which seem plausible (e.g., everyone who bought an individual package later bought the certification package, and everyone gave each package exactly the same rating).

Ok, I've ranted enough about commercialization.

The science of forest bathing

Forest bathing can sound a little woo-woo ("the transformative healing power of nature" etc.), but if we dismiss every alternative healing practice without looking at the data, we might end up on the wrong side of history. So many health practices, from handwashing to vaccination, started out on the fringes of respectability.

As I mentioned, studies show that forest bathing reduces stress, strengthens the immune system, improves cognition and mood, etc.

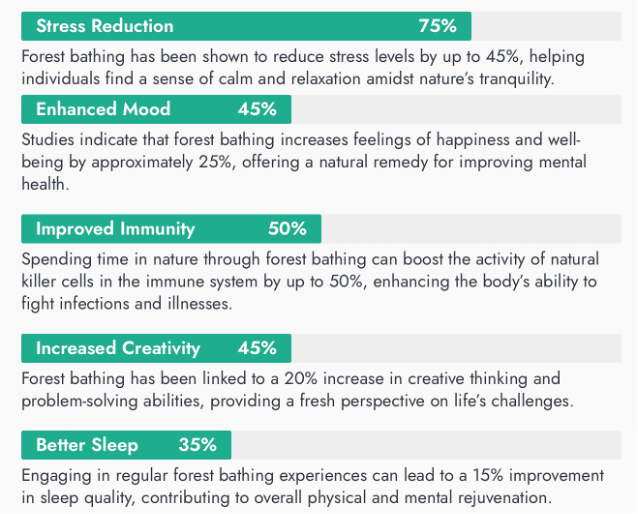

Some of the studies are well-designed, most are not. Plus much is lost in translation when the findings are quoted out of context. For example, the percentages in the screenshot below come from studies with no control group – e.g., people take a walk in the forest and, immediately afterward, they report feeling better.

I'm not sure why the numbers in the green bars mostly fail to match those in the text, but no matter. A leisurely stroll in the woods can surely improve your health. The question is why exactly?

It's not exercise per se. A Japanese team (led by the almost perfectly-named B. Park) has shown that walking in forests reduces stress more than walking in urban settings. In this well-designed study, a 15-minute walk through the forest resulted in lower salivary cortisol levels as well as reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, and other indicators of stress – effects not observed following 15-minute city walks.

Forests don't seem to be essential either, as other studies suggest health benefits from immersion in natural settings such as gardens and parks.

Theories of forest bathing draw on one or more of the following explanations for its healthfulness:

1. Biochemical.

Some experts claim that phytoncides, volatile organic compounds created by plants to ward off insects and microbial invaders, enhance immune system functioning.

Studies do show that phytoncides boost the number and activity of natural killer (NK) cells, white blood cells that kill tumors and viruses, but only at concentrations higher than what we'd experience in a forest. (Plus phytoncides seem to damage T cells, another type of white blood cell.)

The wonderful scents of a forest stem in part from phytoncides. I image that "green exercise" gyms, which are lightly scented with wood oils, smell nice too. Pleasant aromas can be soothing – and therefore good for you – but it's not clear that anything special is happening on a molecular level.

2. Psychological.

Psychological theories hold that urban environments are threatening and require constant vigilance. In contrast, natural settings allow us to relax and recuperate, both mentally and physically.

3. Evolutionary.

Evolutionary theories assume an instinctive tendency to connect with nature that's supposedly frustrated by urban environments.

In my view, psychological and evolutionary explanations rely on overly simplistic, clichéd distinctions between natural and urban settings.

For most of our evolutionary history, nature was not a safe, soothing, pleasant place to unwind. It was often threatening owing to bad weather, natural disasters, poisonous insects, predators, etc. We probably found more comfort in the things we made – dwellings, tools, fire, etc. – than in our natural environment.

Nowadays, our experience of nature can be soothing, but so are many of the indoor habitats we create, as they tend to be predator-free, climate controlled, and replete with food and water. I know people with strong instinctive tendencies to connect with their couches.

Meanwhile, forests may have rough terrain, poisonous shrubs, troublesome insects (2025 has been a particularly bad year for ticks), bears, and/or loud tourists. Plus the weather isn't always pleasant.

Apart from these challenges, forest bathing is simply not an option for people who have limited mobility or insufficient time and resources to get to a forest.

I turn now to a potential remedy.

The new study

This study, scheduled for the August issue of Journal of Environmental Psychology but available now online, was led by Leonie Ascone (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf) and a team of German researchers.

Ascone and colleagues wanted to know which of several virtual reality (VR) forest bathing experiences would best aid recovery from stress.

Part 1: Each of 120 adult participants sat in a quiet, windowless room for 7 minutes.

Part 2: Each participant spent 7 minutes viewing unpleasant photos (examples below). 210 photos were presented for 2 seconds apiece. The point was to create stress.

Part 3: Each participant donned a virtual reality headset and participated in one of the following conditions:

Visual: A 360◦ stereoscopic video of a Douglas fir forest.

Olfactory: An essential Douglas fir oil dispersed via humidifier.

Auditory: A recording of the sounds of a Douglas fir forest (mostly birdsong).

Visual-Olfactory-Auditory: A combination of the previous.

After each part of the experiment, participants completed self-report surveys on their emotional state and performed simple cognitive tests.

Main findings

The only consistent finding was that all four groups showed significant improvements in stress and mood after the Part 3 intervention. Ascone and colleagues were surprised that the Visual-Olfactory-Auditory condition wasn't consistently superior to the rest.

Should we conclude then, as the researchers did, that VR simulations are generally beneficial?

No, because there was no control group.

Recall that as Part 3 gets underway, participants had just spent 7 minutes looking at 210 unpleasant images. I would assume that stress was not just caused by image content but also by their rapid-fire succession. After an experience like that, almost anything would be soothing.

Part 3 should've included a fifth condition, such as sitting in silence, with eyes closed, for 7 minutes. Or, reading a description of a forest for 7 minutes. A non-VR condition is needed to demonstrate the benefits of the VR simulations.

In the end, the study doesn't show that virtual forests are beneficial. Rather, it shows that when you stop upsetting people, they calm down.

(This reminds me of a dumb joke I learned as a kid. Some guy is hitting himself in the head with a hammer. Someone else asks why he's doing that. His response: Because it feels so good when I stop.)

Practical conclusions

No doubt forest bathing is healthful if you enjoy forests. Try it, if you haven't already. But don't assume you need trees.

Both practitioners and researchers emphasize the importance of leaving your screens behind, slowing down, relaxing, and tuning in to the present. In essence, forest bathing is a kind of mindfulness, or mindfulness meditation with a focus on one's natural surroundings.

Studies attest to the health benefits of mindfulness meditation – as well as focused meditation techniques that are suitable anywhere, including indoor settings. John Cage's famous silent piece, 4'33", is a reminder of how many ambient sounds we ordinarily fail to notice or appreciate. The New York Times now offers a 10-minute challenge inviting you to explore a single piece of art for an interrupted stretch.

All this by way of saying that forest bathing is healthful but perhaps not uniquely so. It may not be any more or less beneficial than, say, actual bathing, assuming comfortable water and a quiet room. Anything that both relaxes and engages you can reduce stress and improve your mental clarity and mood. Maybe it's a long walk. Maybe it's your favorite piece of music.

I hate to say it, but strolling through the woods with earbuds seems to work for some people. They miss a lot, but they feel relaxed and restored.

One thing I find especially restorative is Hayao Miyazaki's "My Neighbor Totoro", a quiet film set in rural Japan that's replete with forest scenes. I've watched Totoro with my daughter and now my granddaughters, and I always feel good, thanks mostly to their presence, but also to cinematic magic that doesn't require VR headsets.

Do whatever works for you, as long as it's healthy. The key is to make time to relax and rejuvenate whenever you can.

Thanks for reading!

As always, your analysis was thorough and very helpful in cutting through all the B.S. Thank you.