If you want to look better quickly, you have two options.

One is to change your appearance. It's hard to imagine a time when people didn't do this. Tattoos go back at least 5,000 years, cosmetics may be older, and surely even Neanderthals did something to make themselves more attractive to potential mates.

The other option is to change how your appearance is represented. Historically, this was only feasible for the most privileged members of society. Queen Elizabeth I insisted that paintings of her copy the Darnley Portrait, created when she was 41. Two decades later, she still showed no wrinkles or other signs of aging. (When you're the queen, you don't need Photoshop. One nervous painter will do.)

Cameras democratized the second option, and image editing technology gives 21st century netizens more power over their own image than anything Elizabeth could've dreamed of. Even Photoshop now seems like a quaint relic of the 1990s. Thanks to AI-driven beauty filters, I myself am just a few clicks away from becoming a devastatingly handsome young guy. (In real life, the distance is much more than a few klicks – i.e., kilometers.)

We now have hundreds of thousands of filters to choose from – even Zoom has a "touch up my appearance" feature – and their popularity is growing. A 2021 survey found that 47% of social media users between 18 and 29 have used filters before posting selfies. In 2023, two weeks after Bold Glamor was introduced, TikTok users had already uploaded 18.5 million videos that relied on the filter.

In this newsletter I'll be discussing a new study on the psychological impact of slimming beauty filters, digital tools that can go way beyond plastic surgery in reducing the size of body and face.

I almost didn't read this study. When I heard about it, my first thought was: Why bother?

After all, we've been told over and over again that that idealized, unrealistically enhanced images of people undermine self-esteem, body image, and other aspects of mental health.

We know, for instance, that social media users get trapped in a "validation-seeking cycle" where they post filtered selfies, get a bunch of likes, then feel pressured to continue posting their idealized selves, all the while feeling bad that everyone else looks so damn good.

We also know that girls and young women are especially vulnerable, particularly those whose body type and/or skin tone diverge from the algorithmic ideal, which tends to be slender and Caucasian – or, as Jia Tolentino puts it, "distinctly white but ambiguously ethnic".

I had assumed that cultural critics such as Ms. Tolentino, Zeynep Tufekci, and others, along with data from peer-reviewed studies (as well as Facebook's own infamously-suppressed findings) exhaustively catalog the perils of digitally-curated social media selfies.

Dear reader, I was wrong. The new study may not be perfect, methodologically speaking, but it deepens our understanding of how AI beauty filters affect us. In short, it's a good example of how statistical techniques developed in the 20th century can complement the narratives of the keenest cultural observers.

The new study

This study, co-authored by Makenzie Schroeder and Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz at University of Missouri, appears in the April 2025 issue of Computers in Human Behavior and is available now online.

Schroeder and Behm-Morawitz were particularly interested in how slimming beauty filters influence "social self comparison", their term for what happens when a person compares their actual appearance to a digitally enhanced version.

The researchers made use of SNOW, a free app that can do just about anything to your represented appearance, including radically slimming face and body.

Schroeder and Behm-Morawitz assigned each of 187 adults (average age 36) to one of the following conditions:

Condition 1: Use the slim feature on SNOW.

Condition 2: Watch someone else use the slim feature on SNOW.

Condition 3: Use a polaroid filter on SNOW.

In each condition, one image was created. Specifically:

–In Condition 1, participants created a slimmed-down image of themselves.

–In Condition 2, participants watched a short video of someone else using SNOW to create a slimmer image of themselves.

–In Condition 3, which we might call a control condition, participants created an image of themselves in which the hue of the entire image is changed, but their faces and bodies weren't otherwise affected.

I want to pause for a moment and comment (favorably) on how bare-bones these conditions are. Data on the cumulative impacts of filter use, like anything else, are necessary but tend to be difficult to interpret. This is like a study on what happens when a person smokes exactly one cigarette, or takes exactly one drink.

Following each condition, participants answered questions about body image, desire for weight loss, self-objectification (e.g., how important is "sex appeal" to your self-concept?), and attitudes toward fatness. (The researchers used terms like "fatness", which some would find offensive, but it's clear that no offense was intended.)

Participants also described how extensively they made comparisons to the filtered images while using SNOW (or watching it be used). This meant different things depending on condition:

–Condition 1 and 3 participants were asked "To what extent did you compare your overall unfiltered appearance with your filtered appearance?"

–Condition 2 participants were asked "To what extent did you compare your overall appearance with the person using a filter?"

Participants answered these comparison questions on a 7-point scale ranging from "not at all" to "a lot".

Three key findings

1. Participants who created a slimmer image of themselves (Condition 1) made significantly more comparisons than those in the other conditions did.

No surprise that folks spent the most time comparing their true appearance to a slimmed-down version of themselves. It may be interesting to watch someone else use a filter, but you probably wouldn't spend much time comparing your true appearance to that person's real or filtered image.

2. To the extent that Condition 1 participants engaged in comparisons, they expressed more negative attitudes toward fatness, higher levels of self-objectification, and a greater desire to be thinner.

This is disturbing, but notice that I used the phrase "To the extent that". The data doesn't show that the slim filter is automatically and always harmful. Rather, the filter is only harmful to the extent that it spurs people to reflect on the difference between their unfiltered and slimmed-down images. The greater the amount of reflection, the worse the impact.

This is analogous to the relationship between quality of sleep and risk of a traffic accident the next day. Insufficient sleep increases the risk of an accident, but not automatically. Rather, risk is only increased to the extent that alertness and energy levels are impaired.

Bottom line: Slimming beauty filters may undermine how you feel about your body, unless you can apply the filters without dwelling on how much better your filtered image looks.

3. Participants who used the slim filter (Condition 1) or watched others use it (Condition 2) showed significantly more body dysmorphia than the control group did.

Here there were no differences between Conditions 1 and 2. Body dysmorphia was triggered by the slimming filter, regardless of whether a person used it themselves or watched someone else use it.

(Watching someone use use a filter isn't quite the same as viewing a social media post in which a filter has been used, but still, this finding acknowledges that filters can be harmful regardless of who's using them.)

Why is this study important?

Schroeder and Behm-Morawitz show that slimming filters create harmful effects, and that these effects can emerge after a single use.

Cause-effect relationships

Prior studies report associations between beauty filter use and problems like poor body image, but it was never clear which caused which. Maybe filters undermine body image; maybe dissatisfaction with one's body prompts use of the filters. If dissatisfaction drives filter use, we can't blame the filters for anything. This study indicates that we can.

At the same time, the data doesn't rule out the possibility of cumulative effects. In an email exchange I had this week with Makenzie Schroeder, the lead author, she suggested that using beauty filters over time

"...can result in a compounding effect. In other words, continuing to use filters may make someone feel worse and worse, continuing to drive them toward a desire for weight loss as they keep seeing themselves in this idealized, digital way….

Schroeder also commented on the likelihood of cyclical effects:

"I think filter usage can be a cyclical process. For example, maybe someone uses a beauty filter that digitally applies make-up and reduces the appearance of bumps and fine lines because they do not like the texture of their skin. They then may (hypothetically) engage in social self-comparison, evaluating their digital appearance to be more desirable than their actual appearance. From this, they may be further driven to keep using filters, which could continue to exacerbate how these individuals feel over time…."

Single-use effects

Before reading this study, I would've assumed that the effects of beauty filters emerge somewhat gradually. One use shouldn't hurt. And yet, according to the data, it does. At least temporarily.

This is reminiscent of the finding that smoking one cigarette has adverse effects on the body. The effects may be temporary, but they're a clear warning about the damage that arises from prolonged use.

In the case of beauty filters, single-use effects are worrisome, given how accessible the filters are and how their use is incentivized. A 2018 Pew survey found that 43% of teens feel pressure to only post content that makes them look good to others. Three years later, the journalist Katie Couric made headlines simply by posting a filterless, makeup-free selfie – an act of rebellion against the "Snapchat dysphoria" that has driven some users to obtain plastic surgery to match filtered versions of themselves. "Pressure" seems like an understatement here.

How harmful are beauty filters?

Most of us head out the door each morning looking a lot better than we did when we woke up. There's always the possibility, in theory, of feeling bad that our "true" appearance falls short of what we project via strategic choices of clothing, grooming, and cosmetics.

Schroeder and Behm-Morawitz's study doesn't tell us how much slimming filters exacerbate this problem. The researchers didn't ask people to view images of themselves before and after arranging their hair, for instance, or before and after applying cosmetics. But these are deeply entrenched social practices and arguably among the least problematic forms of personal image curation.

Whatever harm is experienced from pressure to use use cosmetics, it's surely more harmful (even if driven by the same underlying forces) that women are constantly pressured to conform to unrealistic ideals of body size and shape. Slimming beauty filters are dangerous because they offer an unsustainable way of conforming to those ideals, while at the same time reinforcing the implicit message that anyone who needs a filter must have something wrong with them.

How to address the problem

Snapchat says that the goal of its Lens filter is to"provide fun and playful creative effects that allow our community to express themselves freely.”

That statement seems to exhaust the benefits of beauty filters, apart from their use for planning purposes by ordinary folk ("How would I look with different hair?") and plastic surgeons ("How would this patient look with a differently structured chin?")

I would conclude then that the risks of beauty filters outweigh the benefits, given that there are so many other ways to have fun and express oneself freely on social media.

How can we prevent harmful effects? Makenzie Schroeder emphasized the importance of distinguishing between filter types:

"One of the best ways to mitigate the harms of beauty filters is simply by limiting the ones available. For example, social media platforms may consider no longer providing certain filters, specifically those that modify the structure of the body, such as those that shrink noses, lift cheekbones, and slim the face. There are various studies showcasing how these types of filters are harmful, some even prompting cosmetic procedures."

I agree, although it might be difficult to legislate this. Apart from other legal obstacles, I believe social media platforms would get a lot of mileage out of arguing that there's no way to clearly distinguish structural changes from more superficial ones. Since a person can make their face look slimmer via makeup and lighting effects, for instance, how can we define the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable alteration?

Inoculation and support

"All the world's a platform," Shakespeare would write if he were alive now, "and all the men and women merely users. They have their logoffs and their logins, and one person in their time uses many filters..."

AI is so ubiquitous I feel compelled to say that I wrote the previous sentence myself.

Appreciating the ubiquity of AI is also critical to helping manage the psychological threat of AI-driven filters. We have to be realistic and assume their constant presence and accessibility.

In my view, the best strategies for coping with beauty filters start early on in a child's life. Some restrictions make sense, but however much kids are shielded from harmful media influences, we need to accept that exposure will occur. Young people will see porn and violent imagery and disinformation long before we want them to, and they will encounter harmful content and apps on social media platforms, including beauty filters. They need more from us than warnings not to look – or, in this case, not to open the apps.

Here are four suggestions:

1. Help kids accept the faces and bodies they were born with.

This is easier said than done, I know, but it's worth the effort. At minimum, we should avoid commenting negatively on children's physical features – or praising them excessively. (So many parents are still doing one or the other!)

2. Help kids curate their appearance sensibly.

I'll never wear cosmetics, but I have to admit, they do look like fun – if you're not obsessing about every detail being perfect. Same goes for hairstyling and accessorizing and even digital curation – all fun activities if pursued in moderation and without stress. (Again, easier said than done, given how pressuring gender-specific standards of appearance can be.)

3. Recognize vulnerabilities.

Kids differ in how much support they need. Data suggest that those most vulnerable to the harmful effects of AI beauty filters would be girls, children of color, children who struggle with poor self-esteem or body image, and/or children with perfectionistic tendencies.

4. Help kids reflect on the culture.

In Trick Mirror, Jia Tolentino comments on how the pursuit of beauty has become a sort of ethical mandate for women. I wouldn't say that to a 4-year-old, but preteen girls are already well-acquainted with pressure to look certain ways, and I think there's value in helping them deconstruct the cultural forces behind these pressures.

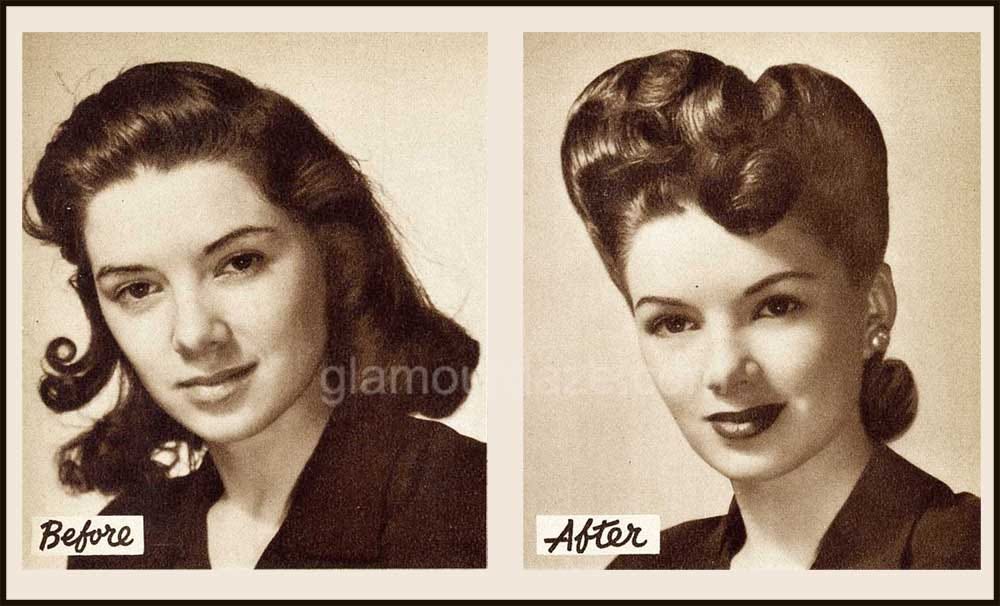

For instance, when my granddaughters are old enough, I'd love to show them this image that accompanied a 1943 interview with a Paramount Studios makeup artist. (Notice that along with other changes, the model's face looks slimmer in the "after" photo.)

During the interview, the makeup artist said

"I wish that every woman would realize that her own personality if correctly enhanced would stop any Hollywood agent in their tracks. Make the most of yourself!....with artful makeup, your real self won't be buried under an artificial mask."

I'd want to tell my granddaughters that (a) Hollywood agents also appreciate acting skills, (b) a Hollywood career isn't necessarily the ideal career choice, (c) there's surely more than one way to "correctly" enhance yourself, (d) "personality" is not what gets enhanced when you wear makeup (!), and (e) artful makeup probably doesn't reveal your "real" self.

I wouldn't literally say this – kids need conversation, not speeches – but these are the kinds of points I might touch on in a discussion of the topic. Instagram Face didn't arise out of nowhere. At its worst, AI exacerbates tendencies that have always existed, including those that motivated whatever the earliest humans did to make themselves more attractive. We're only human, even if AI makes us look otherwise.

Thanks for reading!

More than a few klicks....haha.

Thanks for this look. Seems like this can take the self esteem to another level. Certainly seems to be trying to be compliance with some sort of idealised image that can create disorders like Anorexia or Bulimia nervosa.