Is Healthy Eating Sustainable?

Ah, the smugness of kale.

I mean, don't you want to just camp out in front of McDonalds, sipping a kale-infused smoothie and chiding the patrons for ruining their health and destroying the planet?

Ok, maybe that's just me. And it's probably because I'm jealous. Kale smoothies will never be as tasty as McDonald's french fries, much less smell as nice.

Kale is indeed good for you, and producing it is relatively easy on the environment (low carbon and water footprints, for instance, if responsibly farmed).

On the other hand, most of what McDonald's serves is terrible for both personal and environmental health. (This includes their kale salad, which has more sodium and saturated fat than a Double Big Mac.) Although a $16 McDonald's meal went viral this month, the cost of eating there should be the least of our concerns.

If what I've written so far sounds obvious or even clichéd, well, that was intentional. Like me – and like most of us, according to a new study – you probably assume that healthier foods tend to be less environmentally harmful to produce. The term that gets thrown around a lot is "sustainability". Healthier eating, we assume, is more sustainable eating. We hear about the Planetary Health Diet and infer (correctly) from the semantically-ambiguous name that that the diet promotes the well-being of the earth and its people, with support for one automatically supporting the other.

Are we right about that? If so, are we aware of the exceptions?

These are important questions. What we is eat is determined by lots of considerations (flavor, cost, convenience, etc.), but we also care about our health and the well-being of the planet.

These questions were addressed in the new study I'll be discussing here. This is one of those studies that got zero media attention but, in my opinion, ought to make headlines, because it tells us what we need to know about food in order to promote a healthier population and planet. The study also illustrates some of the diversity in how statistics work behind the scenes to fuel advice on practical matters such as what to eat.

The new study

This study, led by Dr. Gudrun Stroesser (Johannes Kepler University, Austria), was published on November 17th in the prominent journal PLOS Sustainability and Transformation.

The study took place in a dining hall at the University of Konstanz in Germany. Stroesser and colleagues focused on 29 meals served to both students and employees over a six-day period.

Procedurally, the study could not have been simpler: Each participant received a survey to fill out and return with their tray. (On average, 173 individuals per meal returned a survey.)

The main items on the survey were two statements: "My meal of today was healthy", and "My meal of today was sustainable." Participants rated their agreement with each statement on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Also recorded was the specific meal each person had eaten, and some demographic information.

(There's more than one type of sustainability, and the term "sustainable" means different things to different people. In an email exchange with Dr. Stroesser, she explained to me that although the survey did not include a definition of the term, prior research indicates that "environmental indicators are the most salient when people think of sustainable meals." In other words, her participants probably assumed they were rating environmental sustainability.)

The survey responses tell us about perceptions of healthiness and sustainability. Stroesser and colleagues also used a tool created by German researchers to determine the actual healthiness and environmental sustainability of each meal, each rated using the same scale I described above, and thus allowing for easy comparisons between the perceived vs. actual characteristics of each meal. (The algorithmic tool that Stroesser and colleagues used treats sustainability in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and material consumption.)

Results

Although not the main point of the study, I found it interesting that people were moderately accurate in their judgments about the healthiness and sustainability of their meals. The correlation between perceived and actual healthiness was 0.41, while the correlation between perceived and actual sustainability was 0.64. I see this as good news, although there's room for improvement.

Here are the three main findings of the study:

1. Perceived healthiness and sustainability were highly correlated (0.79). In other words, people assumed that healthier meals are more environmentally sustainable.

2. Actual healthiness and sustainability were only moderately correlated (0.42). In other words, there's a genuine relationship between healthiness and sustainability (as has been found in other studies), but the relationship is weaker than participants assumed.

3. Participants were not very sensitive to discrepancies between the healthiness and sustainability of specific foods. That is, they assumed that healthiness and sustainability go hand-in-hand, even when that's not the case.

When you put findings #1 and #2 together, the third one follows, but only by implication. In the Appendix I explain how the researchers provided more direct evidence for finding #3.

Can we trust the findings?

One of the strengths of the study is the relatively standardized treatment of the meals. The researchers knew exactly what participants had eaten. Data analysis was restricted to participants who only ate one serving, and serving sizes were determined by dining hall staff. Data on actual healthiness and sustainability were independently available.

This isn't to say that the measures achieved lab-like precision. I doubt that the dining hall staff counted exactly how many Swabian ravioli they dished onto each plate, and in any case, the actual healthiness of each meal would vary depending on the size and health of the person eating it. Meanwhile, as I've noted in other newsletters, it's inherently difficult to measure complex variables such as "healthiness" or "sustainability". I have some lingering uncertainty too around the way participants interpreted "sustainability". Even if they thought of it environmentally, were they thinking of food production, or production and distribution, or production, distribution, and waste, or…)

(Of course, you could also question how participants interpreted "healthiness.". A person who's trying to cut down on sodium because they have high blood pressure might rate a meal with relatively moderate levels of sodium as unhealthy, even though it is, generally speaking, a very healthy meal.)

I'm sharing with you the kinds of questions you can always ask about data, but in this particular case, I don't think it makes sense to go down the rabbit hole of interpretive possibilities. Why not? Because in this study, a little squishiness in the data wouldn't detract much from the general pattern of healthiness–sustainability overestimation.

In a word, I trust the findings.

Why is this important?

Earlier I complained about the lack of media attention to this study. Why should people know about it?

Well, consider for a moment what might be called "the new groovy" in food sales.

More specifically, think of Whole Foods. Trader Joe's. Central Market (Texas). Erehwon (California). Smaller organic markets. And, nowadays, the organic section of a traditional grocery store. As you probably know, the products sold in these places try very, very hard to persuade you that healthiness and sustainability are one and the same.

I'm old enough to remember a time when food products weren't labeled with humble, deeply sincere, slightly whimsical narratives from the producers, introducing their back story and their particular approach to making you a better person while saving the world.

I have no objection to the new groovy in the food industry. It's nice to know something about the people you're buying from, and a lot of the products are relatively healthy and sustainable. But some of them fall short on one or both dimensions. I mean, Trader Joe's Vegetarian Meatless Cheeseburger Pizza? Way too much sodium and saturated fat. (The product even has extra words in it. If it's "Vegetarian", you don't need to call it "Meatless" too.)

It's hard to say exactly why people link healthiness to sustainability. Sproesser and colleagues talk about the possibility of halo effects (either people think that because food is healthy, it must be environmentally sustainable, or vice versa), but their study wasn't set up to test for this.

I think its fair to say that marketing and advertising have contributed to the perceived healthiness-sustainability connection. The new study offers a clear reminder that we may be overestimating how strongly they're linked.

So, what should we eat? Setting aside considerations of flavor, expense, and convenience, which foods are best for us and for the planet?

The generality problem

In 2010, the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition first published the influential "Double Food and Environmental Pyramid". It's actually two pyramids, arranged side-by-side so that the healthiest and most environmentally sustainable foods are found at the bottom. From bottom to top, both healthiness and sustainability decrease.

The double pyramid model is useful as a general guide. Arguably it's a bit too general. "Vegetables", for instance, do really well, but this doesn't tell us which vegetables outperform others.

(The generality of the double pyramid model is echoed in Sproesser and colleagues' finding of a 0.42 correlation between actual healthiness and sustainability in their dataset. This coefficient tells us that healthiness and sustainability are related, but it doesn't tell us anything specific about individual foods.)

The specificity problem

Through labeling and other sources, lots of data are available on the healthiness of individual foods. I'm grateful for the smorgasbord of information we have now on ingredients, nutrients, and daily values, even if the details are sketchy and the % DV statistics aren't clearly defined on the labels or in the research.

Scientists have gathered much data on environmental sustainability too, but it hasn't been translated yet into simple, actionable recommendations. We don't have anything like nutrition labels for sustainability. Mostly what we have are advertisers' blurbs ("responsibly sourced") and labels that provide, in essence, a thumbs-up.

For instance, we now have "USDA Organic" labels, but they don't tell us much, because "organic" does not equal "sustainable" in any sense. Sometimes organically-produced food is easier on the environment, sometimes not. Same goes for foods that are deemed "Non-GMO Project Verified" or "Certified Naturally Grown".

Treating the sustainability of food as thumbs-up (e.g., organic) versus thumbs-down (e.g., not organic) doesn't seem as useful as the more granular information we get from food labels concerning nutrients. We need detailed, actionable information about sustainability, but all we have at the moment is complex evidence that resists simple generalizations.

For instance, cucumbers create more carbon emissions per serving than peas do, but peas require more water. If you decide to buy peas anyway, you might prefer organic, but a 2018 study found that organic peas create 50% more carbon emissions than traditionally-farmed peas (due in part to a difference in the amount of land used). On the other hand, if you switch to kale, a 2019 study found that organic kale creates 50% less greenhouse gas emissions than traditionally-farmed kale does. Things get even more complicated when you consider variety of kale.

I'm not able to evaluate the science behind these studies, though I can see that experts disagree about fundamental concepts such as how to define and measure carbon emissions. Ultimately, what the consumer is left with is a specificity problem: Too many specific details about each food; not enough clarity about the consequences of our choices.

A solution

Given that the science on the healthiness and sustainability of individual foods is complex but inconclusive, how much information do consumers need to know? I asked Dr. Stroesser about this, and I like what she what she had to say:

"[D]etermining the absolute healthiness and sustainability of foods is not easy. But in the domain of food healthiness, labels for pre-packaged foods have been implemented already in many countries, such as the Nutri-Score in several EU member states. The Nutri-Score includes a simple color-shaded categorization from A (“good”) to E (“not good”)."

"With regard to the potential effectiveness of sustainability labels, a recent review revealed that ecolabels can promote the selection, purchase and consumption of more sustainable food and drinks. The design of a sustainability label could be similar to the design of the Nutri-Score, for example."

In other words, grade the food. And, I would suggest, change that "E" to an "F", so that what we see is like the letter grades we receive in school. Don't get rid of the nutrition labels. Just add a letter for overall healthiness, and another letter for overall sustainability.

If we do this, I will surely write another newsletter someday complaining about the superficiality of grading systems. Still, letter grades for healthiness and sustainability would be an improvement over the information consumers have now – and, as Stroesser and colleagues remind us, we would discover that some foods don't receive the same grade for each.

Thanks for reading!

Appendix: Identifying the healthiness-sustainability overestimation

This appendix isn't essential to understanding Stroesser and colleagues' study. It's just a slightly deeper dive into how they made sense of their data.

The researchers found that the connection between healthiness and sustainability is overestimated. Participants treated degree of healthiness and sustainability as roughly synonymous, even for foods that are higher in one dimension than the other.

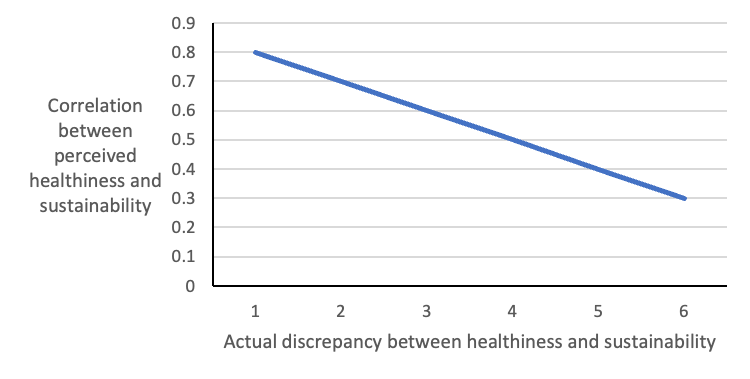

The researchers calculated the extent of discrepancy for each meal under study and analyzed participants' sensitivity to these discrepancies. (Recall that each measure of healthiness and sustainability was rated on a scale ranging from 1 to 6.) The key findings are summarized in the graph below.

(I like this graph. Among other things, it gives you a quick peek into the dining hall experience at a German university.)

To illustrate what this graph tells us, I'll start with a simpler, hypothetical example:

The horizontal, x-axis of the figure above shows actual discrepancy. Foods like kale and Big Macs would receive low scores, because there's almost no discrepancy: Kale is good for you and relatively easy on the environment. Big Macs are bad for you and bad for the environment. As you move to the right, the discrepancy increases. High scoring items would include things like FIJI Water (good for you, bad for the environment) or a six-egg breakfast provided by your neighbor's hen (bad for you, not too bad for the environment).

The y-axis of this figure shows perceived correlation. The higher up you go on this axis, the stronger the perceived relationship between the healthiness and sustainability of some food.

The blue line illustrates what we would hope to find: Close alignment between perceived and actual characteristics. In a word accuracy. That blue line would emerge if people rated kale as very healthy and sustainable, Big Macs as unhealthy and unsustainable, FIJI Water as healthy but unsustainable and a six-egg breakfast courtesy of your neighbor's hen as unhealthy but fairly sustainable.

On the other hand, if people just assumed that healthiness and sustainability are always related, and they aren't appreciative of discrepancies, you'd see something like the pattern below. Here, the blue line is flat and high, because people assume that healthiness and sustainability go together. Healthy foods are sustainable; unhealthy foods aren't.

If you look back at Stroesser and colleagues' graph, you'll see that it's more like the second one I created above. (There's a slight upward trend in the researchers' graph, but it wasn't significant.)