Do good, Hippocrates advised physicians, or do no harm.

What about doing less harm?

Last Thursday, the FDA authorized continued sales of Juul e-cigarettes in the U.S.

The FDA's decision was grounded in the assumption that vaping, though unhealthy, is less risky than smoking cigarettes. Many experts agree.

In this newsletter I want to raise some doubts about that assumption. There are many unknowns, as well as new evidence that vaping might be more dangerous in some respects.

What is an e-cigarette?

"Vape", "electronic cigarette", and "e-cigarette" are all names for the same thing: A battery-powered device that heats an e-liquid until it becomes an aerosol.

My focus is on the most common types of e-liquids, which contain nicotine, flavorings, and humectants.

Humectants, roughly 95% of the e-liquid, suspend other components in the aerosol, and may contribute to flavor and "throat hit". Typically, they're propylene glycol and glycerin (often used create smoke at plays, concerts, etc).

Why is this important?

No surprise that manufacturers and vape shop employees claim that vaping is less risky than smoking. But we hear the same message from health care professionals as well as federal agencies such as the FDA and CDC.

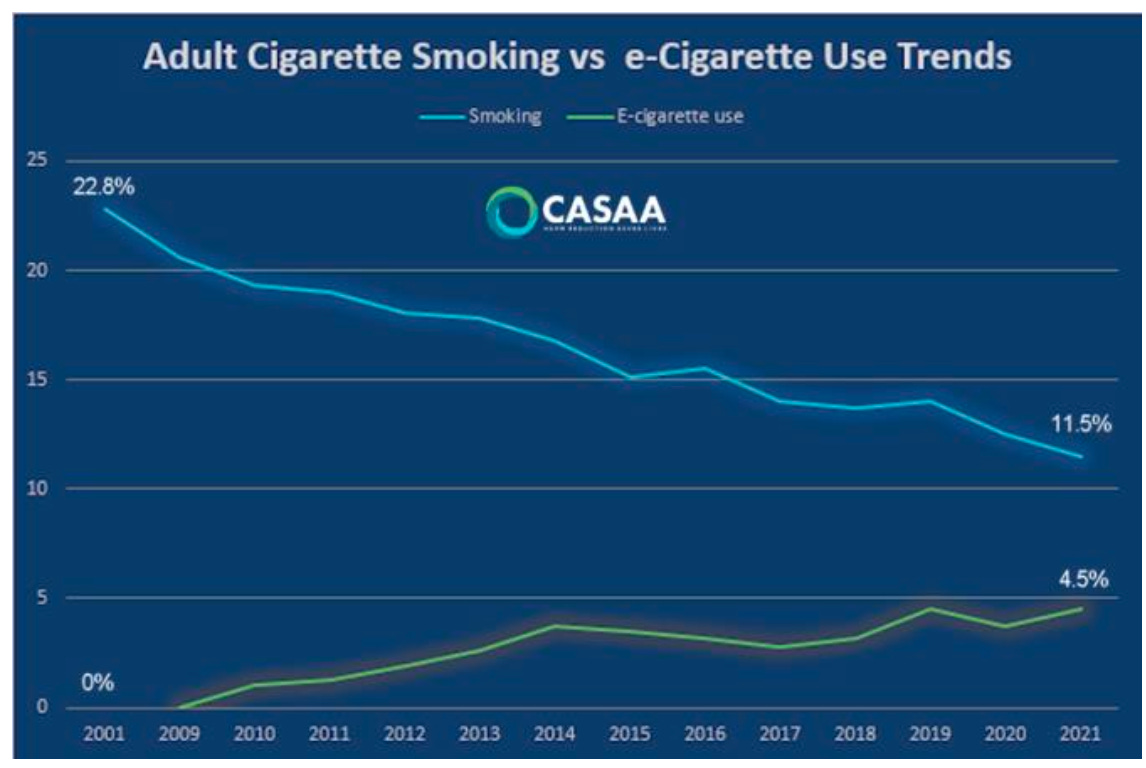

Meanwhile, vaping is becoming more popular among adults as smoking continues its prolonged decline. Nearly 6% of middle and high school students regularly vape too. Although student use has declined over the past 5 years, e-cigarettes are still the most widely used tobacco product among young people.

The vaping industry vigorously supports these trends through lobbying, conventional advertising, and social media influencers. A 2023 study of 54 influencers with over 100,000 followers apiece concluded that "Most influencer posts are unambiguous, branded, vaping advertisments". In addition, only 15.1% of the posts were FDA-compliant.

In short, vaping is a growing, poorly-regulated trend, driven in part by the assumption that it's "better" than smoking cigarettes.

Why is vaping considered less harmful than smoking?

E-liquids are said to contain fewer chemicals – and less dangerous chemicals – than cigarettes do, including less nicotine. Thus, vapers are expected to be healthier than smokers, and switching from smoking to vaping is thought to reduce health risks.

Is this depiction accurate?

Partly. Let's break it down:

—Claim 1: E-liquids contain fewer, less dangerous chemicals.

Tobacco smoke contains more than 7,000 chemical compounds, at least 69 of which are carcinogenic (tar, carbon monoxide, etc.).

E-liquids only contain about a tenth as many compounds (the amount varies from product to product), including some of the same carcinogens (formaldehyde, acrolein, etc.), though typically in lower concentrations.

At the same time, depending on brand, e-liquids may contain hundreds of unidentified chemicals or contaminants. (Less regulation = more unknowns.)

—Claim 2: E-liquids contain less nicotine.

This is a misconception. E-liquids vary widely in nicotine content, and consumers vary a lot in product use.

Here the evidence is clear: Vaping can result in less, equal, or in some cases greater intake and absorption of nicotine. It all depends on the product, frequency of use, and what researchers call the "puff behavior" of users.

—Claim 3: Vapers are healthier than smokers.

Few carefully-controlled studies have directly compared the two groups.

Here's an interesting exception: A meta-analysis published in Women and Birth two weeks ago found that the effects of vaping during pregnancy tend to be comparable to those of smoking (i.e., comparably bad). However, vaping resulted in fewer newborns who were small for gestational age.

This is the kind of research we need – and can expect to see more of as time goes on. In the meantime, there are more questions than data.

4. Switching from smoking to vaping improves users' health.

Here again, there's not much evidence one way or the other.

A few studies show improvement in lung function (e.g., a reduction in wheezing) among people who switch from smoking to vaping, but the research is new and limited in both quantity and scope.

For this reason, HHS agencies and other organizations use cautious language when comparing vaping to smoking. They don't reference health benefits but rather differences in chemical content. For instance, as the FDA puts it:

"For adults who smoke, switching completely from cigarettes to e-cigarettes may reduce exposure to many dangerous chemicals".

Is vaping really less harmful than smoking?

So far, I've hinted that the "vaping is less risky" claim is sensible but overstated.

Now I want to press harder. After commenting on what we don't know, I'll share some recent evidence that vaping might actually be more dangerous.

1. Limited knowledge about long-term impacts.

Modern e-cigarettes, first produced in China in 2003, were not widely used before entering the U.S. market in 2006. Not enough time has passed to understand the long-term health impacts.

For instance, we know that e-liquids contain carcinogens, but we don't know yet whether vaping increases the risk of cancer.

The same can be said for cardiovascular disease:

Vaping causes immediate spikes in heart rate and blood pressure – but then, so does exercise.

Chronic vaping seems to increase resting cardiac sympathetic nerve activity (crudely, an indicator of stress), but the effects are driven by nicotine and therefore not specific to vaping.

A 2019 study that linked vaping to heart attacks made national news, but it was retracted the following year, as some participants may have had heart attacks before taking up vaping. (Oops.)

Along with the unknown, there's the unknowable. Vaping technology is rapidly evolving, and it's unclear what the future holds. Meanwhile, the science hasn't kept up with new product development.

2. Evidence that vaping could be more harmful.

Here are three reasons vaping might be more dangerous than smoking:

(a) Greater nicotine exposure.

Some smokers who switch to vaping end up with lower levels of nicotine (as measured in saliva and urine), but others show no change or even an increase.

Folks in the latter group should be concerned. Nicotine content is the main reason tobacco products are addictive, and the chemical itself, apart from known carcinogens in cigarettes, may contribute to the development of cancer (though the evidence is far from conclusive).

(b) Greater exposure to humectants.

E-cigarette smoke contains more propylene glycol and glycerin than conventional cigarettes do. Lab studies suggest that these chemicals undermine the functioning of epithelial cells in our respiratory tracts. At currently-permitted doses these chemicals may be safe to ingest but perhaps not to inhale.

(c) Greater exposure to heavy metal content.

Conventional cigarettes smoke tends to have higher levels of cadmium, lead, arsenic, and other heavy metals. However, a study published last month found that three particular vape products – Esco Bar, Flum Pebble, and ELF Bar (sold in the U.S. now as Ebcreate) – release much higher levels of heavy metals in their aerosols.

This problem may be limited to certain products, and it may be resolved in future generations of vapes. But it shows that, for the moment at least, e-liquids aren't necessarily less toxic than cigarettes.

The harmfulness of a substance doesn't depend on chemistry alone. For some nicotine users, particularly younger ones, e-cigarettes have more product appeal than conventional cigarettes do:

—E-cigarettes come in more flavors. There are thousands of choices, and hundreds of distinct flavor profiles that, according to an exhaustive 2022 study, include fruit, dessert/candy/sweets, coffee/tea, alcohol, tobacco, mint/menthol, nuts, spices/pepper, and more. (The Flum Pebble ad above looks like a pitch for tropical fruit drinks.)

—E-cigarettes are easier to conceal. They produce less distinct odors (depending on product), no ash or butts, and the vapes can be made to resemble ordinary objects.

As vaping technology develops, we might be concerned that the products are both unsafe and increasingly appealing to younger users.

Final thoughts

Some health professionals recommend vaping as a way to quit smoking.

Some products, like nicotine mints, are marketed as a way to quit vaping.

So, how will people stop eating the mints? Nicotine pouches?

There's a lot of expert advice about how to wean off nicotine products, To help quit e-cigarettes, you can even buy something called the Inhalace, which is essentially a metal straw (see below).

In the end, a key takeaway from vaping-smoking comparisons is that nicotine is addictive, and nicotine delivery systems are dangerous. Trading one poison for another shouldn't be taken lightly (and I doubt that straws alone could be helpful).

A minimal amount of vaping may not increase health risks – the dose makes the poison – but we have no idea what that amount might be.

This brings me back to the FDA's authorization of Juul sales last week.

The legal basis of the FDA's decision is The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, a 2009 law that allows new tobacco products to be sold if they have a "net population health benefit".

The FDA judged that Juul products would have "net benefits" based on evidence that adult smokers often switch from cigarettes to Juul products. The assumption is that the switch reduces health risks.

The problem with the FDA's decision is that vaping hasn't been around long enough to know what happens over the course of anyone's lifetime.

For all we know, people who switch from smoking to vaping eventually switch back.

If they don't, will vaping be less harmful? I hope this newsletter has raised some doubts about that.

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for this insightful examination on vaping. One thing I was looking for was how menthol cigarettes vs vaping affect addiction. There is a propose ban on menthol cigarettes by the FDA but still under review.

"switching from vaping to smoking is thought to reduce health risks"?