I was happy this morning, until I opened my email.

As a former professor of psychology and education, I have no expertise in this field. My only qualification is a working email address.

Academics receive emails like this all the time. Often the sources are questionable. Viruses happens to be a legitimate, peer-reviewed journal that influences science and public policy. For 2,600 Swiss Francs – just under $3,000 dollars – the journal might allow me to have an influence too. Awesome, right?

I woke up happy this morning because I'd temporarily forgotten the election results that had kept me miserable for the past two days.

(That clicking sound you hear is Trump supporters unsubscribing from this newsletter, though it's written for everyone and my ultimate goal isn't partisan.)

The email's spammy request for non-expert input on matters of public health reminded me of the election – specifically, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s now-likely appointment to a cabinet post such as CDC director, or at least a position as health czar, and President-elect Trump's encouragement to R.F.K. to "go wild on health".

I'm actually more qualified than R.F.K. to run the CDC. So are you, I imagine. Because we respect scientific data, in spite of its imperfections. R.F.K. has a history of disregarding science, whether he's promoting raw milk or pushing the fraudulent, discredited claim that vaccines cause autism. Go wild on health? I don't want to hear that from a president. Let him go wild on his own fucking health and leave the rest of us alone.

Sorry, I'm angry. Not to mention resentful, anxious, and uncertain. There's a lot of talk these days about election stress, but that phrase doesn't capture the full range of what many of us are experiencing. What's needed is a more inclusive phrase, like "election distress".

(A therapist named Steven Stosny has described something he calls "election stress disorder," but what I have in mind isn't a disorder. It's just a range of unpleasant feelings stirred up by elections, including the one that just passed and those that will soon determine who controls the House.)

In this newsletter I'll talk about how to cope with election distress, though some of the suggestions could apply to almost any problem. I've interviewed four mental health professionals and will share their perspectives, but my broader theme is that statistics can be a source of comfort too.

Comfort in statistics? I imagine that sounds strange. The simplest way I can put it is that statistics helps us understand who we are and what's most likely to heal us when we suffer. I'll explain what that means as I go.

1. You're not alone.

Two weeks ago, the American Psychological Association released its latest Stress in America poll. Among this representative sample of 3,305 adults, 69% described the election as a "somewhat" or "very" significant source of stress in their lives. That's higher than the percentage for mass shootings (63%), the spread of false news (62%), health care (55%) and a bunch of other pressing concerns.

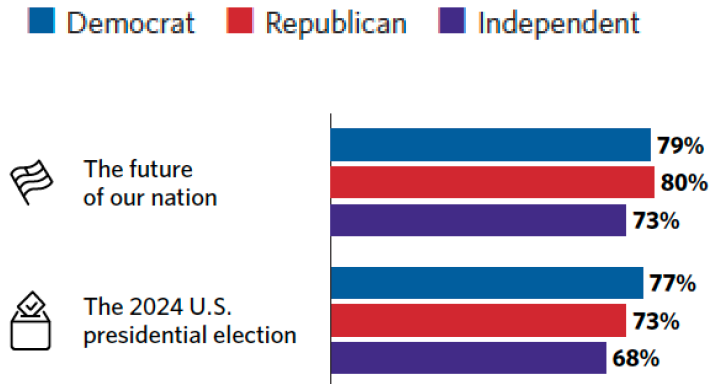

The results of the APA poll were strikingly consistent across political affiliation. As you can see below, most people, regardless of their politics, report experiencing stress over the election and the future of the country.

I suppose we didn't need statistics to tell us this. But news and social media are fallible guides to prevalence, and even reputable journalists can be off target ("I spoke with local residents today who told me..."). In a way, it's comforting to see data confirming that almost all of us feel like we're in this together.

2. We're not as polarized as we think.

"Statistics", from the 18th century German word "Statistik", originally referred to information on the condition of states. Only some of that information, like census figures, was expressed numerically. The purpose of gathering "statistiks" back then was to help leaders govern and promote the well-being of citizens.

In the 20th century, social scientists began to use statistical methods to develop polls and public opinion surveys, and through these efforts, for the first time, societies began to acquire granular knowledge of themselves. Earlier writers might comment on the spirit of the age and the sentiments of different political parties, but with tools like the APA survey, we can now estimate, for instance, that 79% of Democrats and 80% of Republicans acknowledge feeling stress about the future of our nation.

Through modern statistics, we've also come to realize that even though members of the two major political parties tend to dislike each other (or each other's party), the ideological divides are not as great as often assumed. (Rachel Kleinfeld writes brilliantly about this here.)

For instance, here's a two-minute quiz, drawn from a recent report, that I invite you to take right now. If you identify as Democratic or Republican (or at least lean one way or the other), your task is to estimate the percentages of people in the other party who agree with each of the following statements. (Make note of your guesses – I'll provide the answers in a moment.)

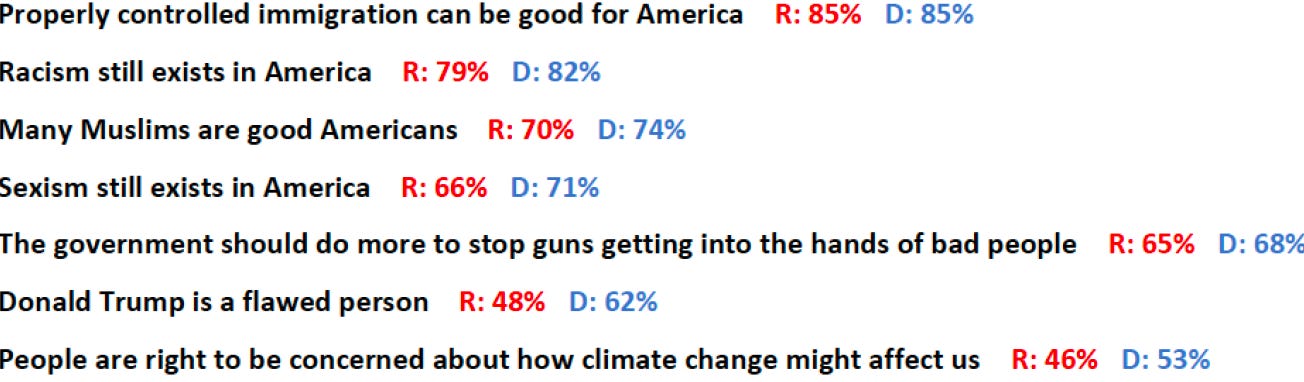

Here are the answers, drawn from a nationally representative survey of 2,100 people:

Two things to note about the statistics:

1. The percentages are quite similar across political party. The biggest difference is for the question about Trump, but even there, only 14% more Democrats than Republicans agree that he's a flawed person.

2. If you jotted down your guesses, you may have noticed a "perception gap" that made your political opponents look worse than you might consider them. This happened for me, as it does for most people.

For instance, I believe that racism and sexism still exist in America (and influenced the 2024 election results), but I estimated that only 50% of Republicans would agree. The actual percentages are 74% and 76%, respectively. In other words, I overestimated the percentage of Republicans who disagree. My so-called perception gap was 14% for racism and 16% for sexism.

I'm not saying that data like this makes me feel better. In fact, I'm kind of dismayed that in 2024, roughly a quarter of Democrats don't acknowledge that racism and sexism still exist in our country. What's most encouraging about the data is the minimal extent of partisan differences.

Of course, a different set of questions could've teased out more polarization. Specific enough questions about gun control, for instance, could reveal a striking partisan divide. My point here is simply that there's more common ideological ground than we realize.

3. We're more similar than different.

Democrats and Republicans are similar in more than just ideology, though that might not be apparent from recent studies in political psychology.

These studies have explored psychological, physiological, and even neurological differences among people with different political views. For instance, several studies have shown that conservatives (or Republicans) are more sensitive to threat, and more suspicious than liberals (or Democrats), a difference that may reflect subtle differences in the ways our brains work.

This tracks with informal observation (e.g., Ezra Klein and Jon Stewart, both separately and together, have noted how traditional distinctions between liberal vs. conservative – or liberal intelligentsia vs. the heartland – are being replaced by distinctions such as belief in institutions vs. conspiracy thinking). All the same, there are some key limitations to these studies:

(a) Small group differences.

Saying that conservatives are more suspicious than liberals is like saying that Germans are taller than Americans. It's true, but the difference amounts to about an inch. Plus, it's an average difference. Lots of Americans are taller than lots of Germans.

When differences are this small and reflect group means (with lots of variability within each group), it's hard to imagine the differences mattering much in real-life settings. One excessively suspicious person may create problems, but an average difference between groups of less than one point on a 7-point scale hardly seems worrisome.

(b) Publication bias.

The notion that Democrats and Republicans differ in psychology or brain function or whatever is intriguing, but the existence of so many studies showing small effects is suspicious. (See, even liberals can be paranoid!) I don't want to accuse anyone of anything, so I'll just say this: Researchers are strongly incentivized to produce this kind of finding, and over the past decade psychology has experienced a reproducibility crisis – i.e., a failure to reproduce some of the small but important effects previously treated as facts.

(Am I overly suspicious? Well, one of those classic studies showing liberal-conservative differences in response to threat, published in one of the world's most prestigious journals (Science), recently failed to replicate. This doesn't mean that all of the studies would, but it's something to keep in mind.)

(c) Overshadowed similarities.

If you look hard enough, you see that either potential similarities aren't being studied (because they wouldn't seem as interesting) or that important similarities do indeed exist.

For instance, a study published last month showed that in the U.S., ideological prejudice is stronger among conservatives when Democrats are in power, but stronger among liberals when Republicans are in power. In short, there's no fundamental difference here between liberals and conservatives: Each group becomes more ideologically prejudiced when their own political party is out of power.

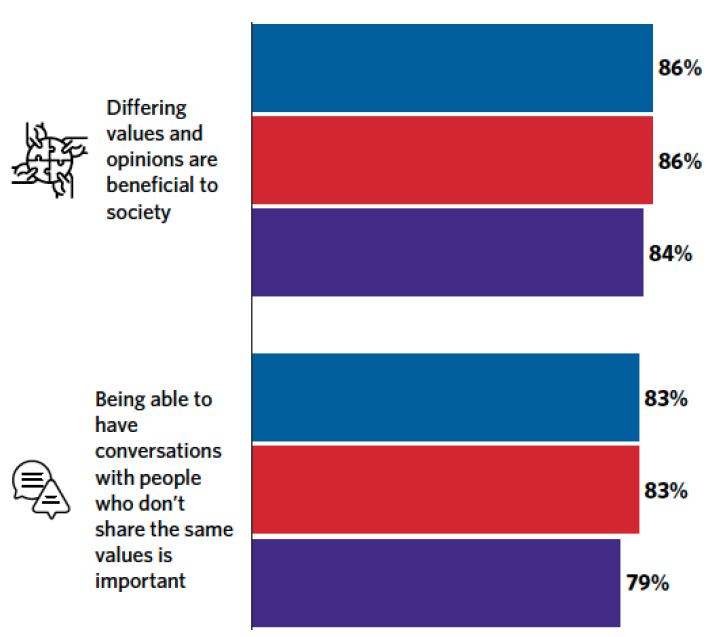

One last example: The APA poll I mentioned earlier showed that most Americans, regardless of party, value diversity in perspective, as shown by the percentage of "yes" responses below (the purple bars are for Independents).

Of course, paying lip service to diversity doesn't mean that a person actually practices what they preach. Some people who answer "yes" to these questions may simply understand this to be the desired response. I still find the data encouraging, because it hints that people at least know what ideals we aspire to.

3. The few create problems for the many.

Speaking of ideals, demonizing your political opponents might make you feel better, but it's not an ideal strategy, because you're condemning roughly half the population. You have to live and work with these people.

When I get frustrated with Republicans, I try to remember that we're more similar than different, and that two factors artificially magnify our differences:

(a) Most elections and ballot initiatives impose binary choices.

Centrist-minded folks may have fairly similar political views but still end up voting differently. A friend of mine "leans Republican", as she puts it, but our views are surely more similar than mine are to those of the most extreme far-left Democrats.

(b) As Rachel Kleinfeld and others have noted, the loudest voices get the most attention – and they're least appreciative of similarities that cross party lines.

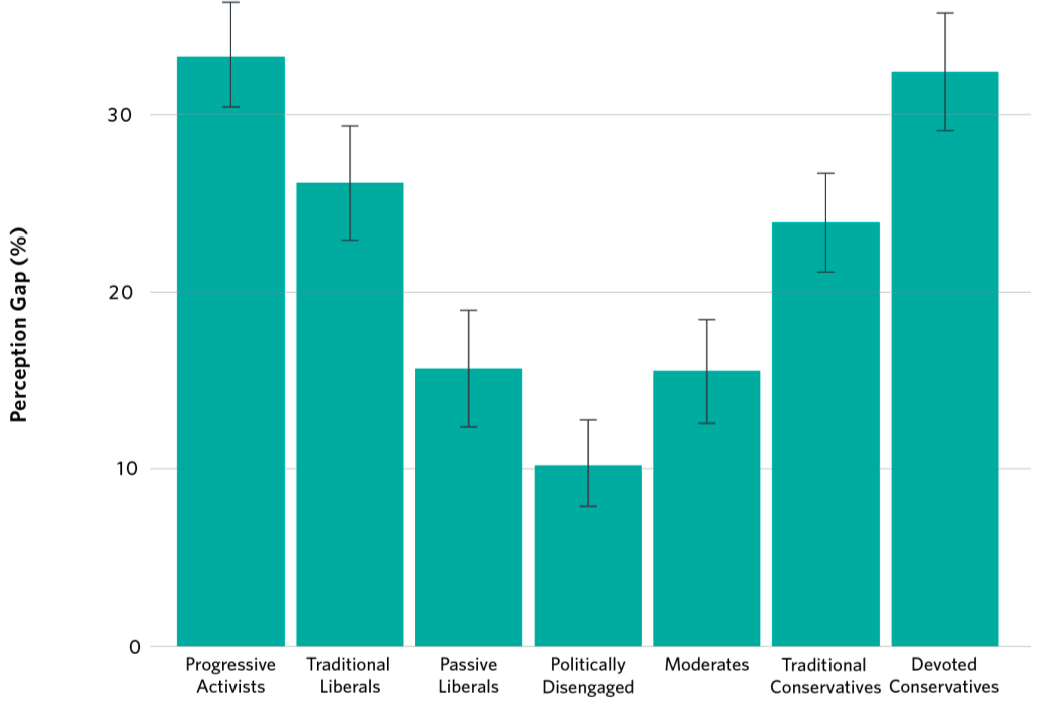

Earlier I spoke of the perception gap – the tendency for those who affiliate with one political party to misrepresent the views of the other. If you took that little quiz, your perception gap score equals the average difference between your estimated percentages and the actual data. The lower the perception gap score, the more accurately you've gauged how members of the other party feel.

Researchers have shown that the perception gap is greatest at ideological extremes. In other words, it's members of the far left and the far right who are least accurate in characterizing the views of their political opponents.

Small-minority effects are also seen for politically-motivated disinformation (e.g., 12 people responsible for introducing the majority of vaccine hoaxes on social media), political violence (mostly committed by a tiny subset of the far right), and voter fraud (an extremely rare occurrence – e.g., 475 potential cases out of 25+ million votes in six of the 2020 swing states).

Here again, I'm not claiming that these statistics, all by themselves, make me feel better. They just help me see the problem more clearly. Often the problem is not the many, but rather the few who create trouble for the many.

4. You can heal yourself.

So far I've suggested that by helping us better understand other Americans, statistics offer grounds for hope. We're not alone in worrying about the future. We're more similar to our political opponents than we realize. And just a small number of people are disproportionately responsible for mutual misunderstandings and other sources of conflict.

Statistical procedures are also helpful in the sense that for roughly a century now, researchers have used them to evaluate techniques for supporting mental health. Clinical and counseling psychology emerged as professions during the same time period and, from the beginning, education and training in these professions relied in part on statistically-based evidence.

I reached out to four mental health professionals for their perspectives. Every one of them mentioned clients with concerns about the election and the future of the country. For instance, Dr. Carly Wielstein, a licensed marriage and family therapist who specializes in trauma and works in a blue state, wrote the following:

"Nearly every single client on my caseload, really anyone 18 and older, has some form of concern over the election or the future of the country going forward. This can range from general fears of the impact of hate speech and discrimination to much more specific and personal fears regarding issues of women’s rights, trans rights, and gun laws. Probably the most common conversation my clients are having though is about grief. Grief related to coming to terms with relationships they’ve lost or had to let go of due to differences and often unreconcilable political opinions with loved ones."

Dr. Stephanie Okolo, a therapist and Army chaplain based in a red state, offered a similar perspective, adding that "many clients feel their sense of security and identity is closely tied to the outcome of the election, which intensifies emotions like anxiety, anger, and sometimes even despair."

So, how to contend with these kinds of election distress?

Accept what must be accepted

You're probably familiar with the Serenity Prayer used by Alcoholics Anonymous and other organizations:

"God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference."

Clichéd or not, the Serenity Prayer came to mind because all of my interviewees referred in some way to its core ideas. For instance:

"I encourage clients to focus on aspects of their lives they can control while acknowledging the power of collective action, which can empower individuals who feel disheartened or helpless." (Dr. Okolo.)

"I encourage people to identify what is and is not inside of their control – this feels particularly relevant when so many things do not feel in our control right now." (Dr. Wielstein.)

One professional, who preferred to remain anonymous (for reasons that will become clear later), noted that

"a few of the people I've been working with lately need a little push to spend less time ruminating on the sorry state of things and more time doing what they can to manage what they have control over, especially their own state of mind..."

This raises the question of what you can do to push yourself to accept what can't be changed (e.g., the results of an election) while attempting to change what you can (e.g., the actions of political representatives and advocacy groups). That's not easy. I agree with something my anonymous interviewee said: It takes practice. You have to keep trying to set aside what you can't control while focusing on what you can. So, here's how I would revise the Serenity Prayer:

"God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, wisdom to know the difference, and motivation to practice doing this every day."

Know yourself

As Dr. Wielstein pointed out, elections may trigger distress without being the root cause of what bothers you:

"...The election and the general state of unrest can be triggering for many people – power imbalances, inequities, the feeling of hopelessness or being overwhelmed – those can bring up a lot of unrelated fears and anxieties for people…"

In other words, if you're experiencing election distress, it might help to figure out exactly what's bothering you. Is it purely ideological?

In my case, I see a mix of rational concerns and more or less irrational animosity. I strongly oppose most Republican perspectives on reproductive rights, climate change, and gun control. I see these perspectives as threatening the well-being of women, the environment, and anyone within range of a firearm. But, to be completely honest, I also hate the fact that Donald Trump gets away with being a scumbag. This isn't entirely rational (there are more important issues at stake), and so the more I can set my animosity aside, or at least figure out what triggers it, the less distress I may feel. Sure, the bad guy wins – for now – but how can I support the good people? And, is there anything in the bad guy's perspective, such as his views on the southern border, that could be transformed into something positive?

I haven't been able to work through my animosity yet, but I take comfort in the thought that my anonymous interviewee experiences a similar problem in spite of his professional experience. Here's what he told me:

"As a therapist I'm supposed to set aside my political beliefs of course and help my clients, regardless of what they believe. But it's hard to shake this very deep, kind of nutty bias that there's just something wrong with a Trump voter. Like, if you follow the news and still vote for this man, there's something fundamentally wrong with your thinking... You're a woman and you're favoring someone who brags about sexual assault against women and taking away your reproductive rights and all the rest? Well, ok, there are some deeper issues we should work on. And I know this is very irrational of me.... I've had to think about this and sometimes redirect conversations with clients so.....my feelings don't get in the way of the support I'm giving... Honestly, I think I need to work on myself..."

Again, we're not alone.

Practice self-care

Trying to understand and directly address a problem illustrates what psychologists call problem-focused coping. This includes what I wrote earlier about understanding the true extent of partisan differences.

Advice like the Serenity Prayer or "know thyself" is problem-focused but also includes elements of appraisal-focused coping or changing one's attitudes toward a problem. Rather than wallowing in election distress, you might start thinking about the source of these negative feelings and whether they're productive. A dismal election outcome could be better viewed as a spur for political engagement.

A third approach consists of emotion-focused coping, or whatever you do to make yourself feel better. This is crucial. I’m not completed comforted by the thought that most Americans aren't as ideologically divided as we assume, or that political engagement is more helpful than animosity.

To cope with negative emotions, Dr. Wielstein emphasizes a mix of establishing boundaries and actively seeking positive experiences:

"I try to encourage clients or anyone to limit media and social media time, take breaks from political conversations or thought process, set boundaries with people or situations that may be provoking or triggering and practice conscious disengagement, even if it is for very short periods of time. I also encourage my clients, or anyone, to actively engage in activities that are distracting or that bring them some comfort or joy. I try to teach my clients that there is a big and important different between “staying informed” and becoming consumed with dread and panic and anxiety."

I like this. The message is to set reasonable limits on exposure to what upsets you, while seeking out whatever brings you comfort and joy.

Dr. Okolo offered concrete suggestions related to specific symptoms:

"For those feeling despair, anger, anxiety, or fear about the election results, my recommendations focus on practical strategies…First, grounding exercises are highly effective in managing immediate anxiety or fear. Techniques like deep breathing, mindfulness, and progressive muscle relaxation can help individuals reconnect with their bodies and center their emotions."

If those techniques appeal to you, the New York Times offers an interactive, mindfulness mediation exercise that anyone can use. Deep breathing and muscle relaxation techniques are also easily found online – a bunch are provided here.

Dr. Okolo also referred to the boundaries on media use that Dr. Wielstein mentioned, while emphasizing, as other therapists did, the importance of social support:

"For ongoing distress, I suggest setting boundaries around media consumption. While it’s natural to want to stay informed, constant exposure can heighten feelings of helplessness. I also encourage finding community support—whether in person or online—where they can share concerns and gain perspective from others. When people focus on the values they hold and channel their energy into meaningful actions, it can counter feelings of powerlessness. Creating space for hope, even in small ways, can remind them that their contributions matter in the bigger picture."

Finally, Vivi He, a licensed professional counselor in a red state, discussed similar strategies while emphasizing self-confidence and growth through adversity:

"For clients with anxiety [related to the election and the future of the country], my strategies to help reduce their anxiety include promoting body relaxation, cognitively reframing thoughts that increase anxiety (such as exaggerating the problem), listing and reflecting on solutions, enhancing self-confidence in handling problems, and helping develop a belief in self-resiliency. The goal is to develop a positive vision of self-growth. Even challenges, failures, and barriers can help us grow."

In short, much can be done to manage the day-to-day feelings of election distress that we experience. For additional discussion of evidence-based strategies, see this article in The Conversation.

Final thought

If you're feeling election distress, I encourage you to try something, and to keep on trying. Try what I've discussed in this newsletter. Try something else. If you don't like my politics, Melania Trump has advice too. The key is to be persistent, because sooner or later something will help – or a new election will come, and you may finally get the candidates you hope for (if not the better America they promise).

One of the "secrets" to better mental health, if there are any, is that once you figure out what works for you, it's likely to help not only with election distress but many other challenges as well. As I said, this is not a partisan suggestion. Though it pains me at the moment to write this, I wish my Republican opponents well too – especially when the next Blue Wave rolls in.

Thanks for reading!

Distressing alright. Great post. Its a hard 4 years coming.

Thanks for this newsletter, Ken! So many individuals are suffering now, and you offer many useful paths to healing while demonstrating your heartfelt concern and empathy. I expect we will need more of that over the next four years.

When elected to office in 2016, Trump’s goal was to dismantle every initiative that President Obama had implemented during his two terms in office. He’s not done with that. I predict he will double down, and I wouldn’t have to be a psychic to tell you that.

Trump and GOP congressional leaders attacked the Affordable Care Act (ACA), aka “Obama Care” on numerous occasions, but it held strong. In 2016, many of us wrote letters to our Illinois congressional leaders, urging them to protect ACA. The Congressman in my District wrote that he had read the alternative Republican plan and thought it was a good one. Later, we discovered that the Republicans didn’t have a plan. Today 45 million Americans are enrolled in coverage related to ACA. But don’t be surprised if the new Administration begins to chip away at that. Why? Because that’s just too much good that’s being done for too many people, due to a Black man who had a vision to make healthcare affordable and accessible to Americans.

Trump was successful, however, in decimating the Pandemic Team that Obama assembled. Now, 1.2 million Americans are dead from COVID 19. I cannot help but wonder how America’s lack of leadership during the pandemic, affected other nations and the entire world.

This man Trump, who proved to us through his actions, that he care little about the health and welfare of Americans, has been given another chance. ACA and other initiatives such as marriage equality, LGBTQIA rights, comprehensive immigration reform, women’s reproductive rights, and sensible gun legislation are likely to be under attack. Let’s stay strong. Let’s be ready to take care of ourselves and each other. ~