Notable Statistics From 2024

Happy holidays, dear reader!

I want to share with you some of the most notable statistics and statistical trends I encountered this year.

My focus is on news, misinformation, and public health, because this is where I found the stats that tell some of the richest and most important stories.

Obviously importance is in the eye of the beholder. Baseball fans will tell you that Shohei Ohtani's 54-59 season is the most important statistic of the year. It's certainly among the most famous. My focus is on stats that weren't so highly publicized but, in my view, should have been.

I'll be describing the "winners" across a variety of categories – a sort of a geeky version of the Academy Awards, except that my emphasis is on bad news. Forgive me for that.

Statistics do provide reasons for hope; I'll share some of those reasons here and more next week. But my "Oscars" mostly honor stats that highlight causes for concern.

1. News/Misinformation Statistics.

Most Disturbing Industry Trend

According to a Northwestern University report released this October, there are now 208 "news deserts", or counties in the U.S. without any locally-based source of local news.

This leaves an estimated 55 million Americans under-informed about their local community (unless someone nearby grows the world's largest pumpkin, or catches bird flu, or otherwise attracts national attention).

News deserts are troubling, because they erode a sense of community beyond one's immediate neighborhood, and because they diminish the ability to influence local laws and practices. Informed citizens can have more impact on a city council or school board, for instance, than on state or federal decision-making.

I also feel terrible for the journalists who are losing their jobs as news organizations scale back or shut down. The Northwestern report notes that 20 states now have fewer than 1,000 newspaper employees.

So, if traditional news organizations are dwindling, where do we get our news?

Most Troubling Consumer Statistic

A November 18 Pew Research Center report found that 21% of American adults regularly obtain news from social media influencers. (For adults under 30, the figure rises to 37%.)

Who are these influencers, and where are they getting their news?

According to Pew, 77% of them have no affiliation or background with a news organization. One hopes they rely on credible sources, but that's not necessarily the case. A UNESCO study released last month found that 62% of influencers worldwide don't vet the information they share.

Our news ecosystem is becoming increasingly gossipy. Statements are treated as news simply because they were stated.

Gossip isn't false necessarily, but it's more likely to be irrelevant, misleading or wrong without the fact-checking and other kinds of editorial oversight conducive to good journalism.

Back in August, when Donald Trump re-tweeted the AI deepfake of Taylor Swift's endorsement, he knew it was a lie. Social media influencers may not know or care about the truthfulness of what they disseminate, much less appreciate that the most important news often includes points of uncertainty or disagreement.

Most Troubling Statistical Pattern

Is it disturbing that 21% of adults get their news from social media influencers, or is it reassuring that 79% of us – the vast majority – do not?

I would only feel reassured if the 79% majority prefers more credible sources. Instead we see a continuing fragmentation of trust.

For instance, here are the results of a nationally representative Associated Press-NORC poll conducted this summer:

What troubles me about this graphic is the small size of the pink segments, the limited variation in the size of those segments, and the relatively large size of the blue ones.

If it's hard to read the percentages, just know that the pink segments reveal no source of information about the government that more than one quarter of Americans trust "a great deal" or "quite a bit" (these are options provided by the pollsters). Ideally, sources like newspapers, news networks, and the federal government itself would inspire substantially more trust than, say, YouTube, but that's not what we see here.

As for the blue segments, many of them approach or exceed 50%. Nearly half or more of Americans have little or no trust in sources that, ideally, would be deemed credible.

These data are consistent with a trend discussed a lot this year: Loss of faith in mainstream institutions.

Ezra Klein and others view this trend through a political lens, arguing that the Democrat-Republican (or liberal-conservative) distinction has incorporated a new dimension: Most Republicans no longer trust mainstream institutions (like news organizations), while Democrats continue to defend them.

I think this is an insightful but overly politicized depiction. Although survey studies do suggest that Republicans as a whole tend to be more suspicious of institutions, this kind of suspiciousness predominates at the ideological extremes in both parties. MAGA Republicans, for instance, are much more vocal these days than moderates. Meanwhile, Republicans of all stripes do trust some mainstream institutions very much (e.g., Fox News).

This leads me to the first of two sources of hope.

(a) The AP-NORC poll question is ambiguous.

If someone asks how much you trust a source of information such as national newspapers, your first thought might be: Which one? I doubt that many people find The New York Times and Fox News equally trustworthy.

Since many of us have close to zero trust in some news sources but quite a lot in others, we might choose the "moderate" option, even though we have "a great deal" of trust in some of the reputable ones.

Thus, the pink segments may be consistently small because people are trying to mentally average across sources that differ a lot in credibility. I find hope in that.

(b) Another source of hope is that what's happening to our news ecosystem seems to involve at least as much realignment as deterioration.

Yes, news coverage is being degraded by the usual suspects (financial pressures created by the rise of social media, the decline of audience attention span, etc.), and yes, AI is making troubling inroads – according to that Northwestern report I mentioned, 45% of journalists reported no AI use policy at their organization – but some of the best journalists are simply moving to non-traditional outlets.

Substack is a perfect example – and it's not only journalists who produce good content here. For recent health-related developments, I trust broad-scope newsletters such as Your Local Epidemiologist, Immunologic, and The Causative Agent, aggregators such as KB's from the Petri Dish, and writers with specific emphases in areas such as adolescence (TeenSights), dental health (Evoke Healing), preventive lifestyles (Healthy Living is Good Medicine), and gun violence (Armed with Reason).

I'm not doing cross-promotion. I just want to emphasize that Substack offers a ton of reliable health-related news, and it's only one of many new players in the game.

Most Embarrassing Statistical Lie

During the holiday season I try to avoid partisan politics, but it's hard to say anything about misinformation without mentioning Donald Trump. Even supporters acknowledge that he has a somewhat casual relationship with the truth.

This August, Trump compared his January 6, 2021 speech to Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" address to the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.

Trump claimed that the audience for his own speech "had the same number of people. If not, we had more."

Reliable estimates suggest that Dr. King spoke to a crowd of 250,000. That's nearly five times as many as the estimated 53,000 who attended Trump's rally. (Ironically, Trump claimed at one point to be seeing 250,000 people in front of him.)

Let's rub it in.

In 1963, the U.S. population was 182.5 million, or just over half the size of our population in 2021 (332 million).

Adjusting for the differences in population, Dr. King's audience was nearly nine times larger than Trump's.

Trump often lies about audience size, but the very triviality of those deceptions makes them important, because they distract from more important ones. Responding to the firehose of lies can lead to exhaustion and a loss of proportion.

As for the speeches themselves, Trump wins on length, but the most crucial differences need no statistical analysis.

"I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood...

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character..."

vs.

"I had to beat Stacey Abrams. And I had to beat Oprah, used to be a friend of mine. You know, I was on her last show, her last week, she picked the five outstanding people. I don't think she thinks that any more. Once I ran for president, I didn't notice there were too many calls coming in from Oprah. Believe it or not, she used to like me. But I was one of the five outstanding people. And I had a campaign against Michelle Obama and Barack Hussein Obama, against Stacey. And I had Brian Kemp, who weighs 130 pounds. He said he played offensive line in football. I'm trying to figure that out. I'm still trying to figure that out..."

2. Health Statistics.

Most unsurprising trend

America continues to spend more on health care than other countries, but we're not the healthiest country in the world. Not by any measure. Not even close.

Typical of the evidence is a September 2024 Commonwealth Fund report. Compared to nine other first-world countries, America ranks first in spending, but last in the performance of our health care system.

Commonwealth's figures, though sometimes light on detail, capture an important point: America is not just different from the other countries. We're an outlier.

For health care spending since 1990, the U.S. is represented below by that dark orange line rising well above the others.

For overall health care performance (as reflected in access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health outcomes), we're that dot way down at the lower right of the figure below. We also finish last on specific dimensions like health outcomes – life expectancy, preventable deaths, etc.

Commonwealth Fund data looks at health care spending as a percentage of GDP, so let's switch to a more focused measure.

Suppose we calculate how much money is spent per person on health care goods, services, and administration. By this metric too, America still pays more for less.

The figure below shows that even before 1990, we were spending more per capita on health care than other industrialized countries do (and as time goes on, that red line moves increasingly far to the right, away from the other countries). And yet our life expectancy almost completely stalls while rising more steadily elsewhere.

This figure extends through 2018, but newer data wouldn't change it much. According to the most recent UN calculations, U.S. life expectancy is 79.5 years. That puts us 48th in the world, right between Panama and Estonia. (At the top of the list is Japan, at 84.85 years, or just over 5 years longer than the U.S.)

If there's any good news here, it's that appreciation of the problem is relatively bipartisan.

—Americans know that a lot of money is spent on health care, because as individuals we're spending it, both on insurance and out-of-pocket costs.

—We also hear a lot about our chronic disease epidemic (rising rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, drug addiction, etc). We hear it in the news and from political figures as divergent as RFK Jr. and Bernie Sanders.

Next week I'll be touching on a recent "health wave" and some other nuances in how we might view the chronic disease trend. But most Americans agree about the fundamental problem: Our country is not as healthy as it should be, given how much we spend on health care. This is encouraging. The first step in solving a problem is to acknowledge its existence.

Most Surprising Projection

The U.S. Census Bureau projects that 30 years from now, the number of centenarians in the U.S. will quadruple.

Currently, about 101,000 Americans are over 100 years old. That number is expected to increase to around 422,000 by 2054.

This is good news if you're a Boomer and hope for a long life. (It's not so good if you're younger and wish we'd get the heck out the way. We're becoming quite a burden for Medicare and Medicaid.)

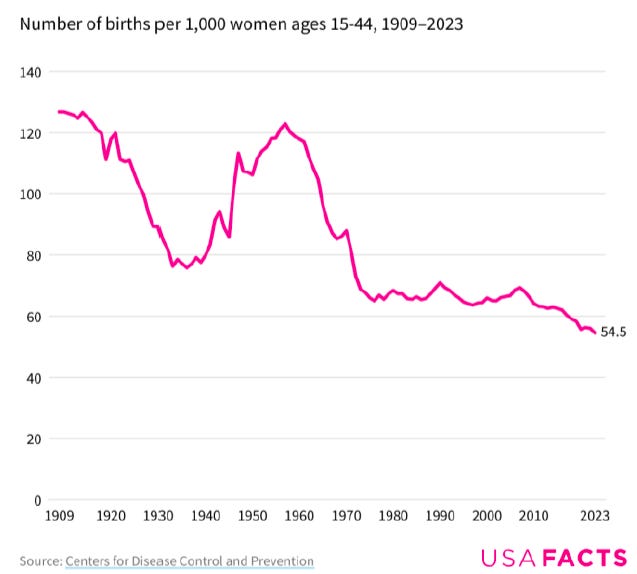

The Census Bureau projection relies heavily on birth rate data. From 1924 through 1954, birth rates increased dramatically. Thus, all else equal, you'd expect a dramatic increase in the number of people still alive one century later.

What makes this projection surprising is the chronic disease epidemic I mentioned earlier, plus the fact that all else is not equal.

In particular, Boomers aren't aging well. A study published earlier this year suggested that by the time they reach their 50s, people born after 1945 tend to be in poorer health compared to those born earlier. CDC data suggests higher suicide rates among Boomers (though rates among younger groups have spiked over the past four years).

Selfishly speaking, I appreciate the optimism about life expectancy. I'd be delighted to meet my great-grandchildren someday. (And if I'm only able to babble at them, that would be positively karmic, since their mothers and grandmother did the same with me once upon a time.)

Worst Statistical Deception

By "worst", I'm referring to a combination of the greatest distortion of statistical data and the greatest impact on public health.

Here we have a tie between James Studnicki, who has falsely impugned the safety of abortion medication, and William English, who has falsely claimed to show that being armed makes private citizens safer.

I do want to live to 100 and meet my great-grandchildren, so instead of delving into the details and causing my blood pressure to spike, I'll just refer you to my posts on these researchers here and here.

As you'll see, what these men have in common is that their data is stunningly bad, they're both outrageous liars, they've both concealed funding from far-right think tanks, and their work has nonetheless found its way into higher court cases, including a few heard by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Most Scary Statistical Misrepresentation

According to a study published in June, having at least one tattoo increases the risk of lymphoma by 21%. The findings were widely circulated in the news and social media.

I've written about this study too. If you or someone you care about is inked, I'm happy to report that the new data has zero credibility.

Those who get tattooed do run a small risk of allergic reactions, infections, and diseases transmitted by contaminated needles. Some tattoos may conceal visible evidence of skin cancer. But there's no credible evidence that tattoos themselves increase the risk of lymphoma or any other form of cancer.

Next week, I will go beyond simply reassuring you that some things aren't as carcinogenic as claimed. I'll be sharing some health-related statistics that offer reasons for hope in 2025.

In the meantime (drum roll, please), the final category.

Most Harmless Statistic

A May 2024 study showed that people find sugar cookies more desirable than sugar-free ones (p < .001).

Who would've guessed? Did you leave the right kinds of cookies for Santa?

Thanks for reading!

Well, exaggerates. But most of us fudge sometimes to make ourselves look better....

I appreciate the work you do. Please keep it up.