The Abortion Pill Debacle

False accusations linger, even after being recognized as false.

This is an example of what psychologists call the continued influence effect. Tell people that John McKenna accepted money illegally, then say wait, it's not true, a typo was responsible for the mistake, and people may still have doubts about McKenna's innocence.

We needn't worry about John McKenna, because he's a fictional character from a 2016 study. But we do need to worry about continued influence effects when false accusations are made about real people and practices.

For instance, research that questions the safety of existing medical treatments can undermine public health even after the studies are discredited and retracted. Perhaps the most infamous example is the 1998 Lancet paper by Andrew Wakefield linking the MMR vaccine to autism.

Wakefield's paper has been discredited in almost every way imaginable – unethical procedures, fraudulent data, financial conflicts of interest, and formal retraction by The Lancet in 2010. No credible data has shown that MMR vaccines cause autism. And yet, fringe groups continue to cite Wakefield's work and treat the man as a sort of martyred hero.

It's heartbreaking to see these continued influence effects – and to see data linking the 1998 paper to increased vaccine resistance and higher rates of MMR.

In this newsletter I'll be discussing another example of research falsely impugning the safety of a medical treatment. The studies in question were retracted less than three weeks ago, but their continuing influence may be uniquely damaging, owing to a case the U.S. Supreme Court will be taking up in late March.

The problem

The Supreme Court will be discussing restrictions on mifepristone, one of the FDA-approved abortion pills. As the New York Times noted recently, the Court's ruling "could preserve full access to mifepristone; impose restrictions...or withdraw approval of the drug."

Loss of approval, or even the restrictions the Court will be considering (no online prescriptions; no delivery by mail) could be devastating. For many women, the laws in their state and/or logistical barriers, such as living hundreds of miles from the nearest abortion clinic, make it effectively impossible to obtain a procedural abortion. For them, medication is the only realistic option. (In the Appendix, I discuss why misoprostol-only abortions, the back-up plan if mifepristone is banned or restricted, may not be an ideal solution.)

I'm deeply disturbed that flawed, retracted studies have led to a Supreme Court case and, as I'll explain at the end, may influence the outcome. If this newsletter is a bit longer than usual, it's because the more I looked, the more reasons I found for concern. In the end, what you'll find here is a sort of case study on how researchers can lie with statistics, and why the deceptions might linger.

Background

In 2000, the FDA authorized the use of two pills, mifepristone and misoprostol, to bring about an abortion. Typically, mifepristone is taken to end the pregnancy, and, one to two days later, misoprostol is used to induce a miscarriage. (Mifepristone is sold under the brand name Mifiprex or as the generic Mifepristone Tablets; misoprostol is sold as Cytosec.)

In recent years, the FDA has made it easier for women to obtain mifepristone and misoprostol. For example, in 2021, acknowledging logistical challenges created by the pandemic, the agency allowed the pills to be prescribed by telemedicine and mailed directly to patients, a change it later made permanent. Currently, the two pills are used for just over half of abortions in the U.S.

Hundreds of studies have shown that medication abortions are effective and safe. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has observed that there's a great risk of complications from wisdom tooth removal, colonoscopies, and Viagra use.

Nonetheless, last April, Matthew Kacsmaryk, a U.S. District Court judge in Amarillo, Texas issued a ruling that would reverse the FDA's approval of mifepristone. Kacsmaryk is a Trump appointee with a history of anti-abortion advocacy.

Judge Kacsmaryk's decision was based in part on the contention that the FDA has not properly acknowledged mifepristone's safety risks. His ruling did not review mifepristone's extensive safety record. Instead, much of the evidence for the health risks of the drug came from two studies led by Dr. James Studnicki, an employee at the pro-life advocacy group Charlotte Lozier Institute.

In April and August of last year, a pair of appeals courts ruled that mifepristone could remain legal, but only under more restrictive conditions – e.g., no online prescriptions, and no delivery by mail. The Justice Department immediately sought relief from the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Court agreed to hear the case this March.

A twist

Although the legal issues are complicated, the lower court rulings would fall apart if mifepristone were assumed to be safe under the various conditions it has been prescribed since 2000.

Less than three weeks ago, Sage Journals retracted three studies by Dr. Studnicki and colleagues, most of whom are employed by the Lozier Institute or other pro-life organizations. Formal retraction of these studies by Sage means, in effect, that the data are untrustworthy and should not be considered scientific knowledge. The twist is that two of these studies figured prominently in Judge Kacsmaryk's contention that mifepristone is unsafe, the foundation for his ruling that FDA approval should be withdrawn.

In short, the U.S. Supreme Court could end up banning or heavily restricting mifepristone based on assumptions derived from retracted, discredited data.

In the remainder of this newsletter I'll be addressing two questions:

1. What's wrong with the retracted studies?

2. Why worry about continued influence effects from retracted studies?

The 2021 study

I'll be focusing on a November 2021 study published in the Sage journal Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology. This is the study that touched off a chain of events leading to its retraction, along with two other papers I mentioned above.

In this study, Dr. Studnicki and colleagues obtained Medicaid data on pregnancy outcomes from 17 states for the time period 1999-2015. Data analysis focused on the 361,924 procedural abortions and 61,706 mifepristone abortions performed in these states during this time period. The outcome variable was total number of emergency room (ER) visits during the 30 days following the abortion.

Two of the key findings were

(a) a higher number of ER visits among women who had taken mifepristone vs. those who had received a procedural abortion; and

(b) an increase in the proportional number of ER visits for both groups from 1999 through 2015, but a higher rate of increase among women who had received mifepristone.

There were additional findings, but they all point to the same conclusion: Mifepristone abortions are less safe than procedural ones. But is that what the data actually shows?

Retraction

In April 2023, Dr. Chris Adkins, an associate professor and Director of Assessment at South University, emailed the editor of Health Services Research and Managerial Epidemiology with concerns about the 2021 study. (As Dr. Adkins mentioned to me in an interview this week, he was not calling for retraction but simply sharing concerns with an editor, as expert readers often do.)

In response to these concerns, the journal's publisher, Sage, reached out to Dr. Studnicki and colleagues, launched a post-publication review process, and ultimately retracted this study and two others. Dr. Studnicki confirmed In a February 13 email to me that he and his team will be pursuing legal remedies for the retraction.

Here I'll describe some of the many concerns that Dr. Adkins and/or Sage raised.

Misleading figures

One of the easiest and most prevalent ways of distorting data is by means of a line graph with an inappropriate range of values on the y-axis.

For instance, let's suppose that you're a used car salesperson at a dealership where most of the staff are selling between 25 and 35 cars per month, and your most successful colleagues often sell more than 40.

Let's suppose too that you haven't been very successful, and so you decide to apply for other kinds of jobs. Since you want to show prospective employers that you've been a good salesperson, you present them with the figure on the left below. (I downloaded these graphs from Wikipedia, so we will also need to suppose that it's 1995.)

According to the figure on the left, you've become increasingly successful at selling used cars. Each year you sell more cars than the previous year, the line rises sharply, and by 1994 you've already reached the highest value on the y-axis.

The problem with the figure on the left is clear. Using 10 as the highest y-axis value is misleading, given the performance of your colleagues at the dealership.

The figure on the right is a more accurate depiction of the same data. Yes, you have been selling more cars each year, but the increase is marginal, and your performance is still quite poor in comparison to that of your colleagues.

Keep this example in mind as I describe a slightly more complicated version of the problem in Studnicki and colleagues' 2021 study.

Dr. Adkins explained to me that his initial concerns with the study were sparked by two of the figures. I’ve pasted in these figures below. If they seem confusing, it's because they are, so please bear with me for a moment while I unpack them. (Also, a semantic note: Studnicki and colleagues use the inflammatory terms "chemical abortion" and "surgical abortion" rather than those standard in science and clinical practice – "medication" and "procedural", respectively.)

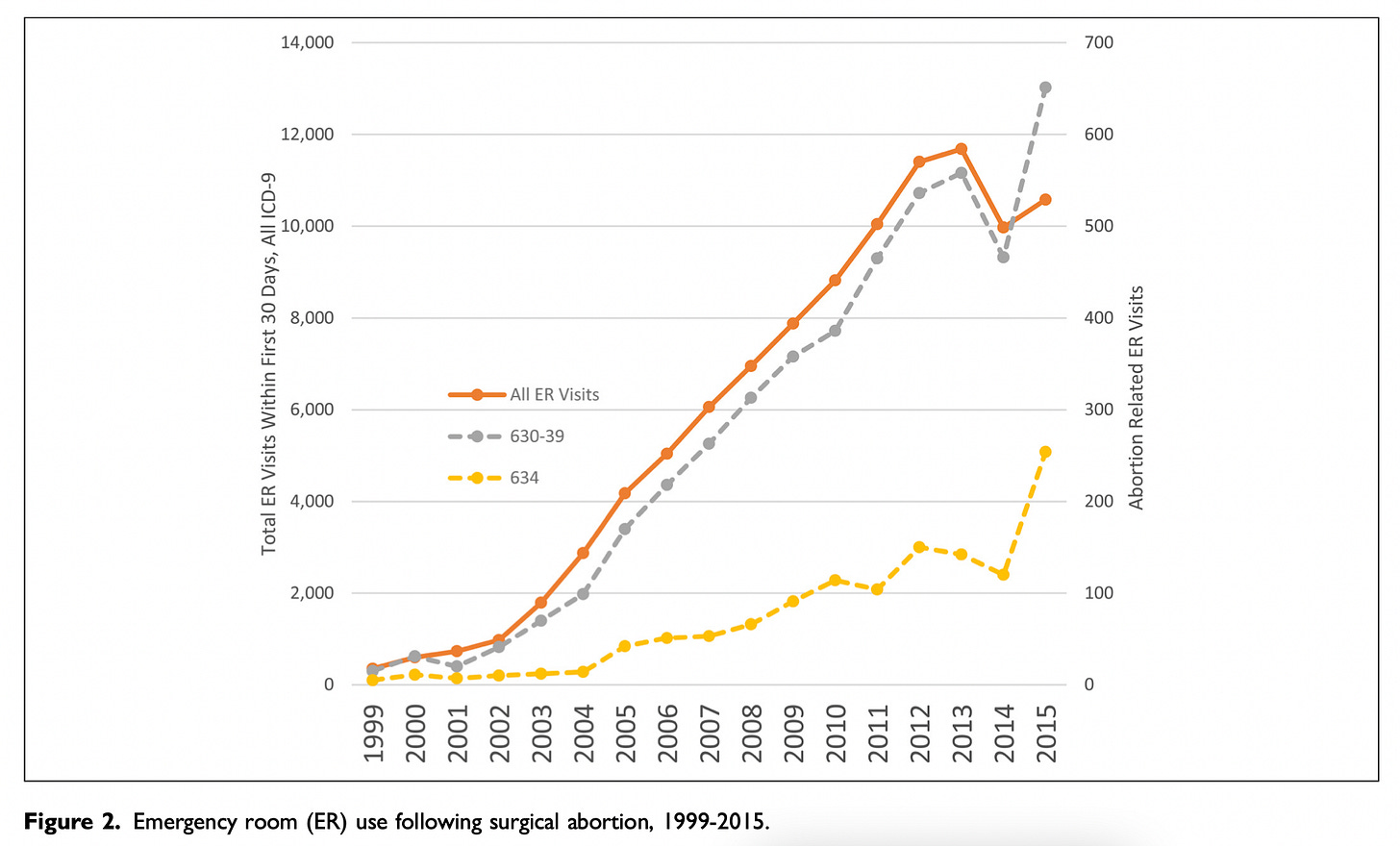

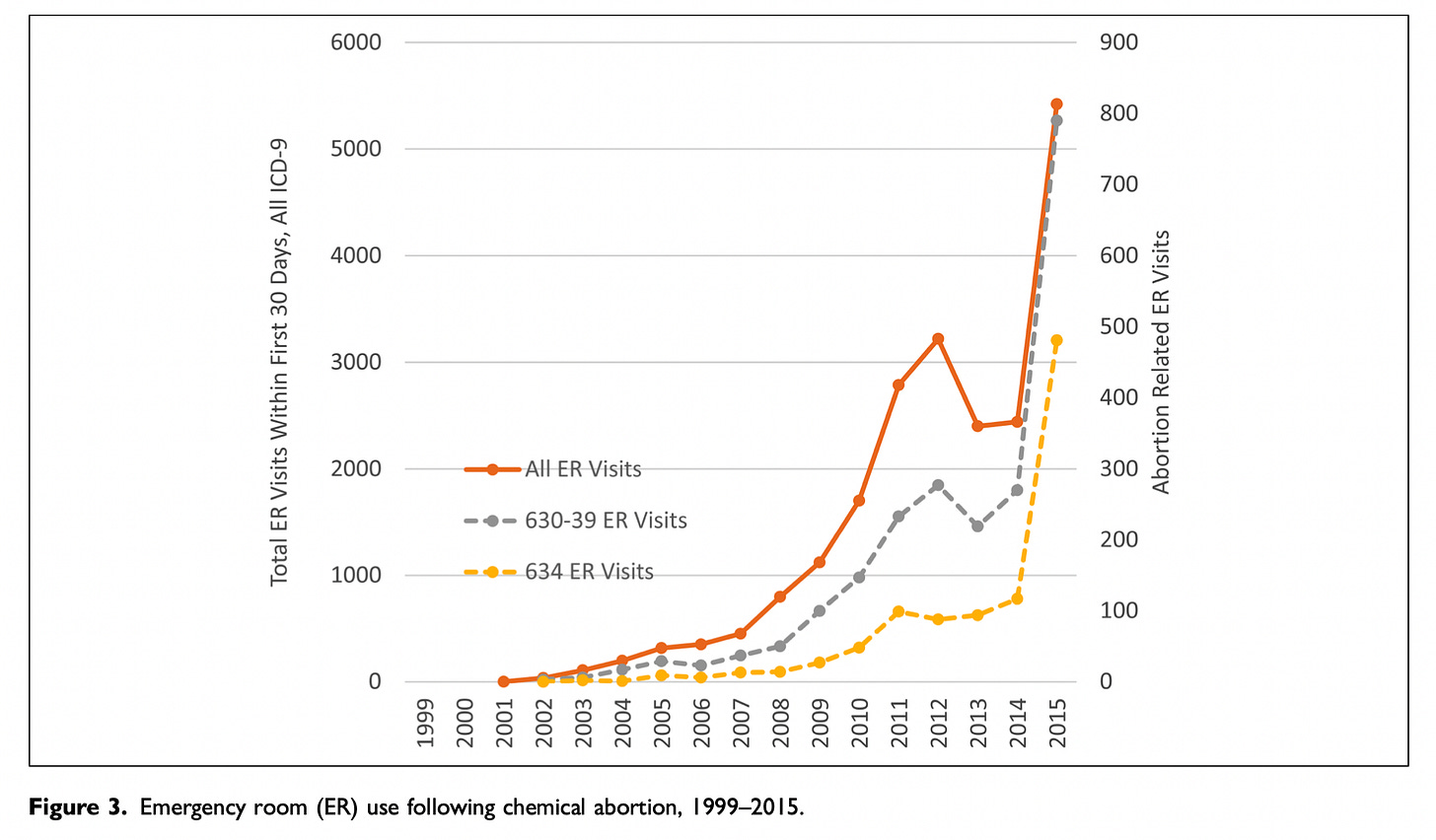

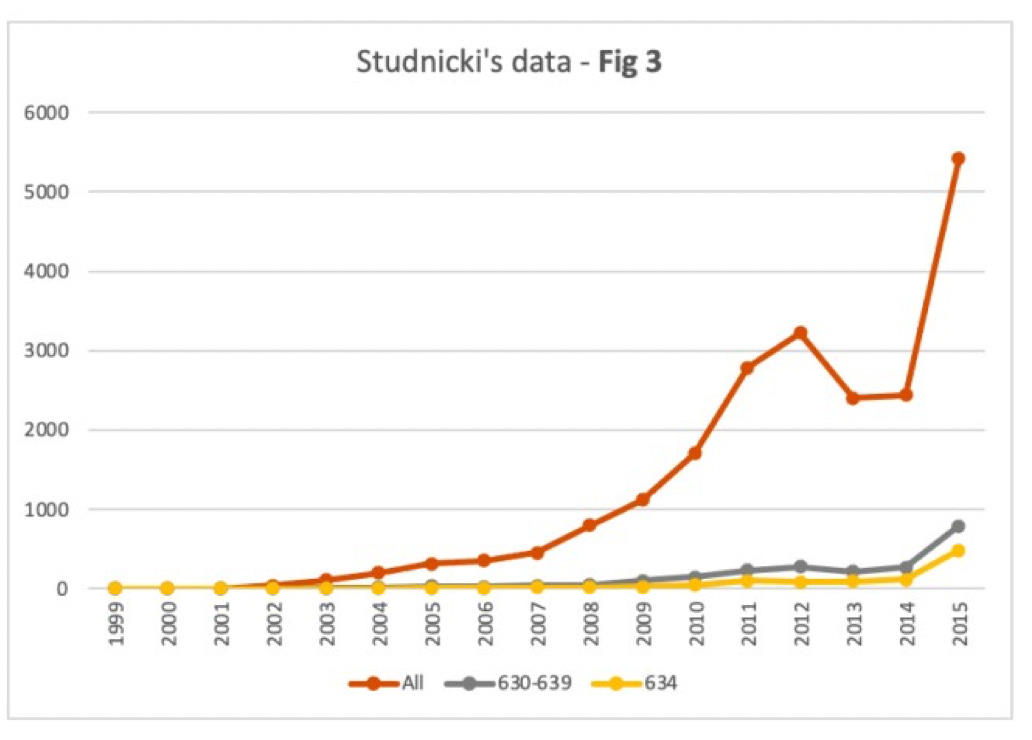

Figure 2 shows data for procedural abortions; Figure 3 shows data for mifepristone abortions.

In both figures, the bright orange line shows all ER visits following an abortion.

The gray line shows ER visits following an induced abortion (procedural in Figure 2, mifepristone in Figure 3).

The mustard-colored line shows ER visits for spontaneous abortions (miscarriages).

In their article, Studnicki and colleagues say this about the two figures: "The steeper growth in total and abortion-related ER visits for mifepristone abortions are apparent in the comparison of Figure 2 (surgical) and Figure 3 (chemical)."

Indeed, the lines do trend upwards more steeply in Figure 3. Taken together, these figures are central to Studnicki and colleagues' claim that mifepristone abortions are less safe than procedural abortions.

Now have a closer look at the figures. Notice anything troubling?

Dr. Adkins did. Sage agreed with his concerns, and so do I: There are actually two y-axes on each of these figures.

The y-axis on the left side of each figure shows the total number of ER visits following an abortion. This axis is meant to be used for the bright orange line. It's not meant for the other two lines.

The y-axis on the right side of each figure shows the total number of ER visits for induced abortions and spontaneous abortions. This is the axis for the gray and mustard-colored lines.

Presenting the graphs this way is misleading owing to the big difference in scale. In Figure 2, the y-axis on the left ranges from 0 to 14,400; the y-axis on the right ranges from 0 to 700. In Figure 3, the y-axis on the left ranges from 0 to 6,000; the y-axis on the right ranges from 0 to 900.

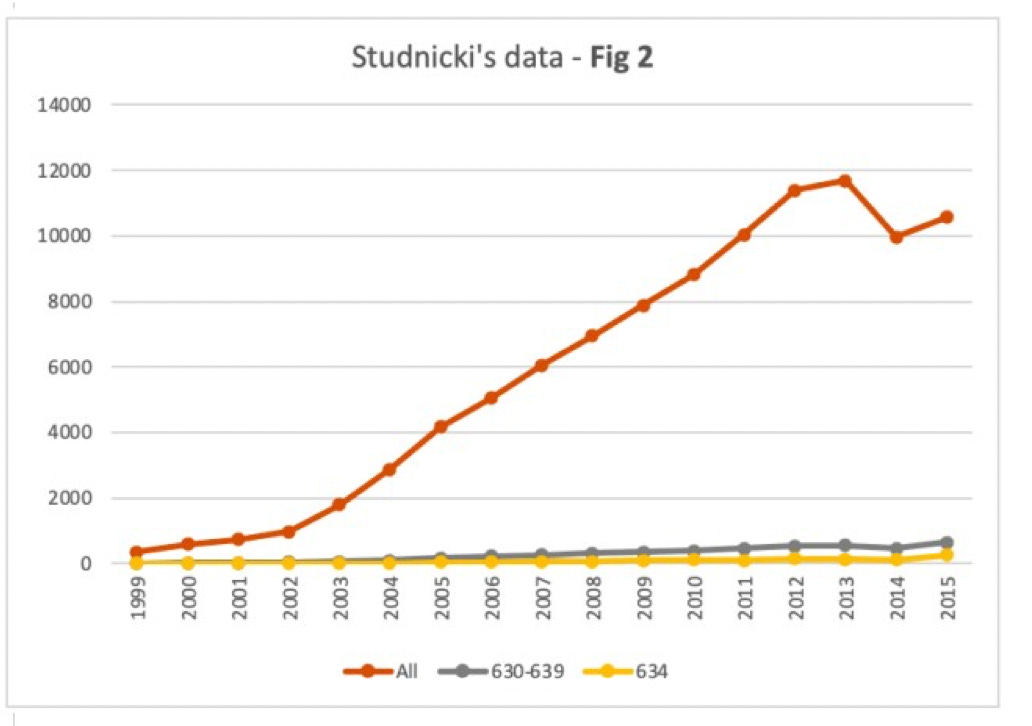

What Dr. Adkins figured out, and what Sage then confirmed, is that once we take Studnicki and colleagues' own data (presented in Table 1 of their article) and create proper figures with a single y-axis, the findings look radically different.

Below are Sage's redrawn versions of Figures 2 and 3, using exactly the same data. As you can see, the gray lines (for procedural abortions in Figure 2, and mifepristone abortions in Figure 3) are now quite flat on the whole.

Now you can see there was very little difference in the numbers of ER visits for procedural abortions (gray line in Figure 2) as opposed to those induced by mifepristone (gray line in Figure 3).

In sum, Studnicki and colleagues' original figures were misleading. They strongly exaggerate differences in the numbers of ER visits following procedural vs. mifepristone abortions.

Studnicki and colleagues claimed later that they used two axes in the interest of helping readers digest the information more quickly, and that any "sophisticated reader" would be able to figure out what the figures convey.

I find this disingenuous and deceptive. A sophisticated reader – indeed, any reader – could only be confused by these figures unless they took extra time to carefully sort out which y-axis corresponds to which line. As Dr. Adkins put it during our interview, "I don't understand why any sophisticated reader...would want that data presented in that fashion."

Studnicki and colleagues didn't help by calling the reader's attention to the difference in scale between the two y-axes. Instead, like the used car salesperson I described earlier, they seemed to have hoped the reader wouldn't notice.

Lack of context

At this point, a pro-life advocate might agree that the figures are flawed and don't actually show that mifepristone abortions are less safe than procedural ones. Still, they might conclude from the bright orange line in each figure that abortions have become increasingly unsafe. Even in Sage's redrawn figures (see above), total ER visits within 30 days of an abortion seem to have risen sharply between 1999 and 2015.

In fact, during the time period explored in this study, Medicaid coverage expanded, and increasing numbers of women obtained Medicaid-supported abortions (and visited ERs for reasons both related and unrelated to abortion procedures). Studnicki and colleagues failed to appropriately contextualize the time-related trends in ER visits, a problem that Dr. Adkins and, later, Sage pointed out.

With an increase in the frequency of any medical treatment, we would expect an increase in complications. The upwardly-trending orange lines in Figures 2 and 3 do not themselves show that abortions are leading to proportionally more ER visits.

The proxy issue

The adverse health effects of an abortion could be measured in many ways. In this study, ER visits were treated as a proxy for adverse events.

Specifically, each time a woman visited the ER during the 30 days following an abortion, that visit was counted as one adverse event. Studnicki and colleagues provided no details on the reasons for multiple ER visits.

Sage's notification of retraction to Studnicki and colleagues points out that their approach artificially inflates the number of adverse events. For instance, if a woman visited the ER on Tuesday due to heavy bleeding, and then returned on Thursday for the same problem, that would be counted in Studnicki's data as two adverse events. In fact, it's just one.

Studnicki and colleagues' response to Sage was to simply disagree. In their words, ER visits provide "an accurate count of the number of adverse events." No clear rationale for this statement was given.

In the study itself, the researchers didn't even note how many women visited the ER multiple times versus just once. As Dr. Adkin's noted during our interview, a prudent researcher would've included that information.

I reached out to Dr. Studnicki via email for additional clarification. His response, on February 13, was just as simplistic as what he told Sage: "We see no ambiguity or error in counting each ER visit if it occurred on a separate day..." Once again, no rationale.

This feels like I just told a little boy: "You were wrong to steal your sister's toys, because they belong to her, and it makes her sad when you steal them, and you shouldn't be stealing things anyway...." And the little boy keeps stamping his feet and saying: "No, I was right!"

Each ER visit is an ER visit. In the absence of further information, you simply cannot know whether each visit is for the same reason or a different reason as the previous one, and it is surely a mistake to count multiple visits for the same problem as separate problems.

Deceptive framing

When ER visits increase from 15 to 45, you can say that the number of visits increased by 30. You can also say there was a 200% increase. Both statements are true.

When ER visits increase from 1,015 to 1,045, you can also say that the number of visits increased by 30. However, in this case the percentage increase is tiny – just under 3%.

Studnicki and colleagues took advantage of the fact that mifepristone was first authorized for use in 2000, and thus, during the earliest years they examined, very few women obtained mifepristone abortions. For instance, in 2001, their dataset included only 15 women who had used mifepristone. In contrast, 9,986 women received surgical abortions that year.

Thus, for instance, when the researchers wrote that ER visit rates per thousand abortions for the mifepristone group increased by 507% from 2002 through 2015, a reader might be taken aback unless they notice that in 2002 this group only had 36 ER visits.

Throughout the article, Studnicki and colleagues mixed sensationalized and sensible approaches to presenting descriptive data, frequently shifting between relative and absolute values.

Dr. Adkins mentioned to me that he had to read the article several times to keep track of these shifts. I had the same experience. I find it hard to attribute the shifts to anything other than a desire to selectively exaggerate effects.

Ideological bias

The ideological commitments of the researchers are clear and represent a plausible explanation for flaws in methodology and presentation of data.

Even if you didn't notice the affiliations of the researchers, you might detect something distinctive about the language used in the article, such as Studnicki and colleagues repeated references to mifepristone abortions as "chemical abortions". As Dr. Adkins notes, "that's not a medically accepted term in the health care field. It is one term that has been adopted by certain groups to stigmatize, and it's kind of a scare tactic. It's an exploited term."

(Ideological bias can also be seen in the lower court rulings that relied on Studnicki and colleagues' work. For instance, Judge Kacsmaryk also used the term "chemical abortions" and referred to abortion providers as "abortionists." His focus on Studnicki and colleagues' data, at the expense of hundreds of studies demonstrating the safety of mifepristone, is clear evidence of bias as well.)

Dr. Studnicki, the lead author on all of the retracted studies, is Vice President and Director of Data Analytics at the Charlotte Lozier Institute, described on its website as the "research and education institute of Susan B. Anthony Pro-life America." Susan B. Anthony Pro-life America is a pro-life advocacy organization whose mission, in its own words, is "to end abortion".

Although Sage's retraction is based in part on nonpartisan methodological concerns, such as those I've described here, Studnicki and colleagues are treating the retractions as a purely ideological decision. The Lozier Institute calls the retractions a "meritless" assault on science, and warns that "Big Abortion and their allies think they can silence pro-life Americans by silencing pro-life researchers...."

The retractions are not meritless, as I've demonstrated here.

The retractions are not about Big Abortion, whoever exactly that is. It's about a journal signaling that articles have been found to report untrustworthy data. (According to Sage, it's also about authors who failed to adequately note conflicts of interest.)

The retractions are also not about silencing pro-life researchers. It's about a journal "silencing" untrustworthy findings once profound flaws had been brought to light.

I'm actually unsure whether I agree with Sage's decision to retract the articles. If a few corrections were added, I wouldn't find the studies to be substantially worse than many others of relevance to public health (some of which I've picked on in earlier newsletters), and the conflict of interest issue is tricky. The key difference is that Studnicki and colleagues' research is at the heart of a Supreme Court case that could significantly undermine the quality of life for women seeking access to legal abortions.

Bottom line

Dr. Adkins raised additional concerns with the 2021 study, as did Sage during their separate post-publication review process. Studnicki and colleagues' point-by-point rebuttal strikes me as deeply unpersuasive.

The small number of concerns I touched on in this newsletter converge on a simple conclusion: The data do not show that mifepristone is unsafe. Rather, the data tell us nothing. The studies illustrate flawed science driven by an ideological agenda, and perhaps a dozen methods of statistical deception.

Final thoughts

At the outset I mentioned concerns about continued influence effects.

When Justice Department lawyers argue their case before the Supreme Court next month, they will surely make note of the decades of research attesting to mifepristone's safety, as well the retractions of key studies. Without those retracted studies, Judge Kacsmaryk's contention that the drug is unsafe is backed by very little other than a mix of anecdote and the FDA's own data (which merely shows that, like other medical treatments, adverse effects occasionally occur).

Unfortunately, retraction may not be enough to prevent continued influence effects. Studnicki and colleagues will be pursuing legal remedies for Sage's retractions on the grounds that they were ideologically motivated. The Supreme Court is unlikely to adjudicate the legality of the retractions, or to wait for some lower court to make the decision. Rather, they're likely to proceed under the cautious assumption that it's unknown at present whether Sage had been in the wrong.

In other words, the Court may not view the retractions as evidence that the data are untrustworthy. If they don't, the data will exert a continued influence effect. ("Perhaps Sage broke the law, perhaps Studnicki and colleagues identified genuine safety concerns...")

The Department of Justice can push back against this by emphasizing the decades of research on mifepristone's safety, and walking the nine justices through the kinds of issues discussed in this newsletter. But one might ask whether Brett Kavanaugh is willing to have a close look at the y-axes in Figures 2 and 3? Or whether Clarence Thomas wants to hear about the ambiguities of using ER visits as a proxy for adverse events? Perhaps, perhaps not.

My fear is that some of the justices will simply decline to engage with the details of the science. They will say that in spite of mifepristone's remarkable safety record, some studies raise doubts, and it's unclear to what extent their retraction was ideologically motivated. The Court will then view FDA's actions through the lens of uncertainty about mifepristone's safety and uphold restrictions or impose a ban, leaving many women with an additional burden when seeking a legal abortion.

There's some debate about how much the Supreme Court can be influenced by public opinion, since the Constitution doesn't require it. All the same, I think it's worth making your opinion known. Suggestions for how to do that can be found here and here.

Thanks for reading!

Appendix: What happens if mifepristone is banned or restricted?

Misoprostol can be used by itself to bring about an abortion. The side effects tend to be more severe than when used with mifepristone, and its effectiveness at completing the abortion is slightly lower, but it is a viable alternative used in a number of countries.

Although abortion providers in the U.S. have said they will immediately switch to misoprostol-only prescriptions if mifepristone is banned or restricted, this would represent a shift to slightly less favorable option for women with respect to safety and effectiveness, and, I suspect, it may only represent a temporary solution.

Even though misoprostol has an independently-established safety record (it was approved for preventing ulcers caused by NSAIDs and is used off-label for abortions), the few studies in the U.S. questioning the safety of medication abortion technically don't distinguish the effects of this drug from those of mifepristone, since both are taken to induce abortion. If decades of research attesting to the safety of mifepristone can be questioned in legal settings on the basis of a small number of flawed studies, the door is open to the allegation that the combination of mifepristone plus off-label use of misoprostol is unsafe. One or two more flawed studies could support this allegation.

In his email to me, Dr. Studnicki indicated that in spite of the retractions, his team will be continuing to gather data that extends the retracted studies. In my view this is a cause for concern.

thank you for this