The Great Crime Disconnect: Part 2

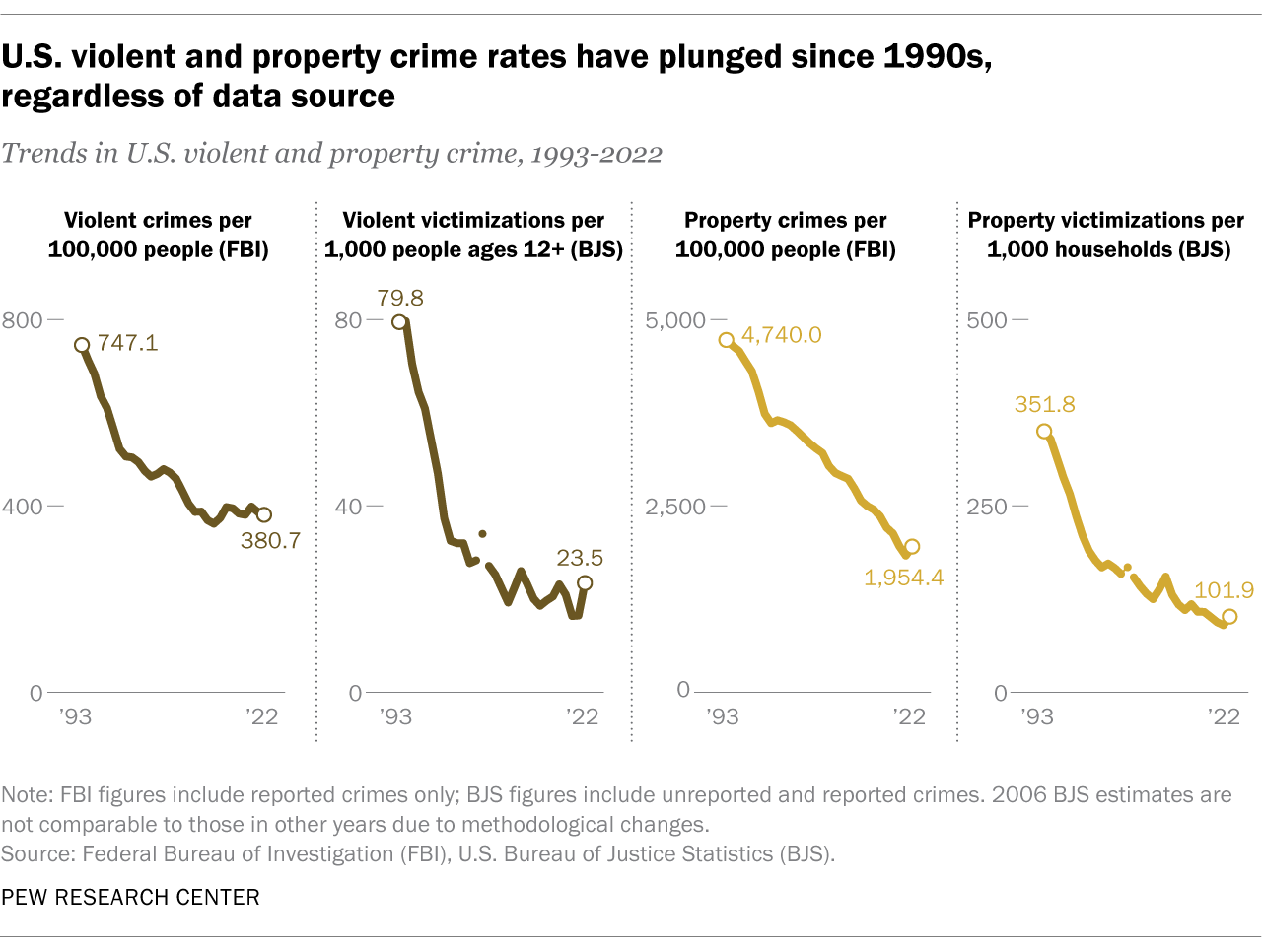

Crime rates in the U.S. have been dropping since the 1990s, a trend that criminologists and other experts sometimes call the "great crime decline".

Surveys show that most Americans believe that crime is increasing. I call this the "great crime disconnect" because for nearly two decades, public perceptions have been out of step with the evidence.

Last week, I shared some of the data on crime rates and public perceptions. This week I'll discuss why crime has been declining in the U.S., what we can do to support this trend, and, in the Appendix, where public misperceptions originate.

The problem

There are lots of hypotheses for the drop in crime. More than 35, according to University of Chicago criminologist John Roman.

Why so many hypotheses? A key reason is that in the 1990s – as in any era – there were many kinds of social change. Pick one and say, that's the cause for the crime drop, and you may have just chosen something that only coincidentally occurred around the same time.

Treating coincidental associations as genuinely related is referred to as spurious correlation. For instance, Tyler Vigen notes that since the late 1990s, the popularity of the name Monica has been highly correlated with the marriage rate in Nevada:

Obviously, the declining number of Monicas is not causing Nevadans to avoid marriage. Mr. Vigen could only find such a close association (r = 0.995!) by running more than 600 million separate correlational analyses.

If you added violent crime to the graph above, that line would overlap with the other two. But, clearly, reductions in Monicas and Nevada nuptials don't explain the crime drop.

Recognizing correlations as spurious whittles down the list of possibilities a bit. For instance, following are three widely discussed hypotheses that mostly reflect coincidence. (I say "mostly" because, in each case, the hypothesis describes something that may have helped reduce crime, but only slightly, if at all.)

The better economy hypothesis

The idea that economic growth in the 1990s resulted in less crime has been discredited. For instance, lower unemployment rates and higher wages for low-income workers result in fewer property crimes, but in each case the influence is small, and it doesn't extend to other types of criminal activity (e.g., violent crime).

In specific times and places, economic factors do have a strong impact. In the 1990s, GM closures of automobile plants in Flint, Michigan put many residents out of work and led to spikes in criminal activity. But this illustrates a local effect that occurred in response to extreme disruption. Overall, crime rates don't simply drop as the economy improves.

The concealed carry hypothesis

In the late 1990s and early aughts, some scholars argued that new concealed weapons laws reduced crime because criminals became more wary of potential victims. This hypothesis is still popular among gun-rights advocates. However, as Freakonomics author Steven Levitt has observed, this hypothesis predicts the strongest impacts on face-to-face crime, a pattern that has never been found. (Besides, in recent years, relationships between concealed carry laws and crime rates have largely disappeared.)

The capital punishment hypothesis

As the death penalty became much more common in the 1990s, some scholars viewed it as a deterrent that reduces crime. This one of the clearest examples of a spurious correlation. The most obvious limitation of the hypothesis is that it doesn't explain reductions in crimes that carry no risk of a death sentence. (In other words, most crimes.) Some studies find that implementation of the death penalty doesn't even lead to declines in homicides.

The security hypothesis

Having ruled out the better economy, concealed carry, and capital punishment hypotheses, we're still faced with a long list of evidence-based possibilities that may not be spurious. How can we sort through the data without getting lost or glossing over key details?

One approach is to lay out standards for a valid hypothesis, then check which hypotheses meet those standards. The most influential (and useful) example I've seen of this is in a 2014 paper by University of Leeds criminologist Graham Farrell and colleagues.

Farrell and colleagues argue that a valid explanation for the post-1990s crime drop has to pass four "tests". Specifically, it has to be consistent with

(a) crime drops in other countries during the same time period,

(b) changing crime rates before the drop,

(c) rises in specific types of post-1990s crimes (e.g., cybercrime), and

(d) variation in crime drops across time, place, and type of crime.

Farrell and colleagues evaluated 17 hypotheses and found that only one passed all four tests. Not surprisingly, it's one that Farrell himself had been pushing and continues to favor: The security hypothesis, which links the drop in crime to increases in the quantity and quality of security devices.

The security hypothesis works well for certain kinds of crimes. For instance, crimes involving forced entry into businesses and homes in the US, UK, and many European countries declined after the introduction of burglar alarms, deadbolts, surveillance cameras, and other security-enhancing technologies. These technologies were introduced at slightly different times from country to country, and, in each case, the crime drop only began after the technology came online. Similar patterns have been observed for auto thefts.

Apart from explaining declines in burglaries and auto thefts, Farrell et al.'s tests are useful because they rule out some (but not all) of the other hypotheses. Here I'll describe two of the most famous ones that failed: The abortion law and lead reduction hypotheses.

The abortion law hypothesis

The 2005 book Freakonomics is an international bestseller and the foundation of a wildly successful media franchise – additional best sellers, a blog, a documentary film, podcasts, an NPR segment, etc. Lead author Steven Levitt, a University of Chicago economist, is a renowned expert who attracts much scholarly heat for mishandling data in the interest of catchiness.

Sometimes it's hard to tell whether Levitt's critics are motivated by genuine concerns or professional jealousy, but there is one claim in Freakonomics that got a lot of attention and is now mostly discredited, thanks in part to data showing how badly it fails some of Farrell's tests.

In Chapter 4 of the book, Levitt and co-author Stephen Dubner claimed that the legalization of abortion in 1973 contributed to a decline in crime in the 1990s. Based on one of Levitt's earlier papers, the authors argued that legalized abortion reduced the births of children who would've been most predisposed to crime – specifically, children whose mothers were unmarried, teenage, and/or poor. Without legalized abortion, these children (particularly the boys) would've reached young adulthood during the 1990s and kept crime rates high.

"This theory is bound to provoke a variety of reactions", wrote Levitt and Dubner, "ranging from disbelief to revulsion..."

Indeed. The theory also provoked a closer look at the data. Farrell and colleagues, for instance, pointed out that it fails the first, third, and fourth of their tests. Links between abortion access and diminishing crime roughly two decades later aren't observed in other countries. The abortion law hypothesis can't explain rising rates of certain types of crime (e.g., cybercrime). And, when you look closely, it doesn't explain some crime-specific discontinuities, like burglaries and thefts beginning to decline shortly before violent crimes do.

The abortion law hypothesis has other merits and limitations I haven't mentioned here, but you get the idea. Levitt remains an advocate, but the hypothesis is widely discredited. (In retrospect, it was a particularly difficult one to test, given the time lag between cause and effect.)

The lead reduction hypothesis

In the early aughts, a number of scholars developed some version of the following argument: Lead exposure damages the brain in ways that reduce impulse control and increase aggression. Children are especially vulnerable to the effects of lead. Thus, reductions in lead beginning in the 1970s led to reductions in crime beginning roughly two decades later.

This is another especially difficult hypothesis to evaluate, in part because laws regulating the use of lead in gasoline, plumbing, paint, food and beverage containers, etc. emerged over a period of decades beginning in the 1970s. A 2022 meta-analysis does suggest small effects for homicides and violent crimes, at least through 2009. Overall, though, the lead reduction hypothesis fails several of Farrell and colleagues' tests (e.g., it doesn't explain increases in violent crimes between 1925 and 1985, when exposure to lead was high, nor does it account for increases in cybercrime in recent years, when lead exposure has been relatively low).

Why this isn't the end of the story

So far I may have created the impression that 16 explanations for the decline in crime since the 1990s fail to hold up, and the only one left standing is Graham Farrell's security hypothesis. Certainly Farrell and his supporters believe that. But it's not the end of the story.

(a) The security hypothesis may explain declines in auto thefts and forced-entry crimes, but deeply ad hoc speculations are needed to explain reductions in other kinds of crime. For instance, Farrell and colleagues suggest that forced entry and auto theft are gateway crimes. Because security technology deters those crimes, there will be fewer perpetrators who move on to more serious crimes, such as assault and murder. I find this about as plausible as the notion that marijuana is a gateway drug. Most people who use marijuana don't end up taking fentanyl. And, those who use both may start with marijuana only because it was more readily accessible when they were young.

(b) Not everyone agrees with the way Farrell and colleagues read of the data. For instance, they rule out the internet hypothesis, which they define as a decline in crime that occurred when the internet began to occupy the time of young people who might otherwise engage in crime, and when cybercrime began to replace traditional methods. Farrell et al. argue that the crime drop was already underway by 1994, when the internet first became widely accessible in the U.S.

The problem with this argument is that the "internet hypothesis" actually consists of two different claims. The first claim makes sense: The internet arrived too late for us to say that crime dropped because potential criminals were suddenly obsessed with AOL. However, the second claim fails. There's convincing evidence that as cybercrime emerged, it did siphon away some of the criminal activity that had formerly been carried out in physical spaces.

(c) Farrell and colleagues relied on a binary approach to evaluating hypotheses: Each hypothesis either wins if it passes all four tests, or loses if it fails one or more. They describe the losing hypotheses in vague language (e.g.,"failed" or "playing little or no role"), which rules out factors that may play small but meaningful roles. I'll return to this point later when discussing policing and incarceration.

(d) From a policy perspective, and from the perspective of an ordinary citizen (i.e., you and me), Farrell and colleagues' approach is too stringent. If a hypothesis for the crime drop accurately describes what happened in the U.S. but not in other countries, they don't consider it a valid explanation.

In fact, if we were sure we knew why crime fell in the U.S., and it was some factor we have control over, the information would be important and actionable. Scholars could still puzzle over the mystery of why crime dropped in so many other countries in the 1990s, but in the meantime, we could make our own streets safer.

So far I've suggested that the crime drop in the U.S. is attributable in part to improved security technology, and in part to the replacement of physical crimes by cybercrime (which may or may not yield a net drop, since cybercrimes are especially difficult to quantify). I want to turn now to what I consider the most powerful influence.

The stronger community hypothesis

In his 2018 book Uneasy Peace, Princeton sociologist Patrick Sharkey argues that the crime drop can be attributed mainly to the strengthening of local communities via organizations that promote neighborhood well-being.

It's an appealing book. Sharkey is a fairly good storyteller, and he seems willing to follow the data, even when it leads to unpleasant conclusions.

In particular, he acknowledges that increased police presence and mass incarceration both contributed in small but meaningful ways to crime declines since the 1990s. (Farrell and colleagues reject both hypotheses; Levitt and many others argue that both play a role.)

Sharkey acknowledges the dark side of these influences – more police can result in more police violence, and mass incarceration has an extremely disruptive impact, particularly in communities of color. Still, following a classic theory in sociology, he sees policing and incarceration as part of a system of "capable guardians" that help preserve public order.

Some of these factors are "guardians" in a literal sense. For instance, Sharkey discusses the revitalization of the Hollywood Entertainment District, formerly a seedy, crime-ridden part of Los Angeles that tourists would tiptoe into for photos before scurrying away. In 2000, a group of business owners pooled resources and created an 18-block business improvement district (BID) that included patrols consisting mainly of off-duty or retired police officers. Crime rates declined (and a later study showed that crime was not simply displaced to other parts of the city).

Sharkey's main emphasis is not on BIDs but on community organizations that provide support and training to adults, as well as safe places for students to congregate after school, communal gardens, and other accessible facilities. He attributes the crime drop in Los Angeles to the influence of community organizations such Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles (CCSCLA), which organized block clubs, provided training and other support to former prisoners, monitored crime and dumping, and helped build properties.

The security hypothesis is folded into Sharkey's theory – he notes that CCTV cameras reduce crime – but this is just a small part of the transformation of public spaces he finds consequential.

At the same time, some of the benefits of community outreach arise from stand-alone programs rather than organizations. A Los Angeles example that Sharkey didn't mention is Kris Edstrom's Student Stress and Anger Management Program, which supports students throughout the LA Unified School District. A recent evaluation showed that the benefits of SSAM participation include increased self-esteem, better stress management, lower absenteeism, and a 73% reduction in weekly anger frequency and violent behavior. The evaluation data doesn't pertain to crime per se; rather, it shows that SSAM positively impacts students in ways that other studies link to reductions in criminal behavior. (Kudos to Ms. Edstrom!)

As for direct measures, Sharkey himself gathered data on the construction of community organizations and programs and found that for each 100,000 people in a city, every new organization intended to improve safety and build stronger neighborhoods leads to a 1% drop in violent crime and murder, as well as other reductions in crime. It's the organizations and programs, of course, as well as the devotion and persistent outreach of their people that matter.

Cornerstone Crossroads Academy

This brings me to Cornerstone Crossroads Academy and its Executive Director, Dr. Kristi Lichtenberg, one of my personal heroes. CCA and Dr. Lichtenberg are excellent examples of the kind of organization and person that Patrick Sharkey describes as instrumental to reducing crime, even though CCA is not actually a crime prevention organization.

As described on its website, CCA is as "a second-chance high school helping students ages 17-25 earn a diploma, discover their purpose and find pathways to success through rigorous academics, holistic case management and supportive vocational training." The school is located in South Dallas, one of the poorest and most crime-intensive areas of the city.

CCA students contend with a number of challenges that most high school students don't experience. Some are homeless, some are single parents, some have guardians who are incarcerated or struggle with addiction. And yet, these students tend to be successful, thanks to Ms. Kristi (as she's known to everyone at CCA), her principal Wayne Sims, and devoted staff such as graduation counselor Billy Rose.

Along with academic support, CCA's case manager helps students with practical issues like medical needs, access to driver education programs, and document procurement. Students take classes in financial literacy, job readiness, and people skills – three areas that could use more attention in conventional public high schools. The school is faith based, and so both academic- and non-academic support is grounded in an ethical framework. And, CCA takes a "family-style" approach to education, which means, among other things, that the 20 or 30 students and staff on campus at any one time tend to problem-solve as a community (and experience the support as well as tensions of any close-knit family).

During the 2022-2023 academic year, 18 CCA students received their GED or a traditional diploma. Almost all of them are now employed or attending community college.

I reached out to Dr. Lichtenberg this week about Sharkey's thesis and the impact of CCA. She mentioned (and Sharkey touches on this) that a distinction can be made between local community organizations versus large ones led by people from outside the community, noting that both types may be needed for benefits such as crime reduction, but

"the first type seems to stabilize neighborhoods, while the second type almost seems to foreshadow gentrification. In those cases, community organizations get a foothold in an area and seem to create a pathway for the developers to come in and start taking properties lot by lot and house by house."

Gentrification is nice for residents and those who come for the coffee shops, but there's no evidence it leads to city-wide reductions in crime. Rather, studies show that gentrification only reduces violent crime in gentrified areas (while sometimes increasing robberies). A 2023 study in Philadelphia, the first of its kind, showed that gentrification simply displaced violent crime to other parts of the city.

Dr. Lichtenberg is concerned that the gentrification already beginning in South Dallas will continue to expand, forcing residents into even more crowded residential spaces and contributing to a recent spike in crime there:

"We speculate that one reason for the uptick in crime in our little area is that people are getting herded into smaller and smaller areas and feeling more and more threatened by the development. There's a sense of despair over losing family homes and the communities that have nurtured hopes and dreams."

Dr. Lichtenberg and her people are addressing these trends by "making efforts to help homeowners get their paperwork in order, i.e. filing for homestead and senior property tax exemptions, making sure properties are in the right person's name, helping with wills, etc."

As for the uptick in crime, one issue not captured by the statistics or even in much of Sharkey's book is that support is needed for more or less instantaneous decision-making. Not all crimes are premeditated. As Dr. Lichtenberg puts it,

"We have the privilege of working with young people who are making decisions daily about whether to move toward or away from crime… In an instant, they have to assess the situation and determine whether to stay or leave, depending on who's there and what other activities are happening around them. Last week, two of our young men were hanging out at their apartments when someone started shooting…"

I noticed quite a bit of discussion of prudent decision-making during visits to CCA, along with the strong emphasis on academics, mutual respect, collaboration, and maintaining a sense of purpose.

Kudos to Ms. Kristi and her supporters!

What can we do?

We've come a long way from Cesare Lombroso's once influential theory that criminality is inherited and you can spot criminals from the way they look. Lombroso, an Italian scholar who may have coined the term "criminology", laid out this theory in an 1876 book, around the time scientists were amassing brain collections and seeking to find anatomical features correlated with criminal tendencies (see my earlier newsletter on brain growth).

One of the many problems with Lombroso's theory (apart from being wrong) is that it's not actionable in any satisfying way. Eugenicists often cited Lombroso as part of their rationale for sterilizing criminals and other undesirable types.

Some of the hypotheses that fail to explain the crime drop would also be hard to put into practice. It's not easy to change the economy, or the laws pertaining to capital punishment, abortion, concealed carry, etc.

In my view, the most effective means of reducing crime – strengthening communities – is something we can all contribute to. You can support community organizations like CCA and programs like SSAM with your money and/or your time and/or simply by spreading the word. Voting behavior, particularly at the local level, can be helpful too.

Of course, making use of security technology can keep us safer (we don't need criminologists to tell us that). As for police presence and incarceration, the fact that they may reduce crime to a small but meaningful extent doesn't automatically justify expanding them. As Sharkey and others point out, we should weigh the benefits against the costs. Currently nearly 1% of the adult U.S. population is incarcerated. That's a shocking statistic that looks worse in light of racial disparities in incarceration rates, the economic and social costs of keeping people behind bars, abuses associated with the increasing privatization of prison facilities, criminogenic effects (the influence of time served on future criminal behavior), and other serious fallout.

On the other hand, if our communities can be strengthened, we won't need as much incarceration in the first place.

Thanks for reading!

Appendix: Why does the American public believe crime is increasing?

If the data shows that crime has been dropping since the 1990s, why do the majority of Americans think it's increasing? Why the great crime disconnect?

Last week I mentioned concerns about the accuracy of the survey data. I also noted that for certain years (e.g., 2020), survey respondents wouldn't have been wrong in saying that crime had increased since the previous year. For most years though, public perceptions do seem to be inaccurate.

Most explanations I've seen mention something about media coverage (murders make the news; the absence of murder doesn't) and political partisanship (conservative outlets are more crime-focused). I believe these are relevant factors, but I don't think they're presented properly. They feel like a recipe with the steps described out of order.

Gallup data is most commonly cited as evidence that Americans generally think crime is increasing. In a 2022 poll, for instance 78% of respondents said that the nation had experienced more rather than less crime since the previous year.

However, when the data are broken down by political affiliation, it turns out that 92% of Republicans and 58% of Democrats said that crime has gotten worse. (I'm leaving Independents out of the discussion, as well as some muddiness in the data I discussed last week.)

In short, to simplify a bit, virtually all Republicans, but only a little more than half of Democrats, believe that crime is increasing. Year after year, this is the pattern that Gallup reports.

Rather than beginning with the usual premise that the majority of Americans think crime is increasing, our starting point should be the existence of two fairly distinct groups of Americans, and the possibility that we need a different explanation for each group.

For Republicans, I'd argue that the misperception is driven by media coverage. I ran a little "study" this morning to illustrate.

On the Fox News website, I entered the search term "crime rates" for the date range January 1, 2024 through today. 11 of the first 12 hits concerned increasing crime rates and used terms like "soaring" and "surges", usually in the headlines. I saw the same thing in the next 6 hits and decided to stop counting because, you know, once you've seen enough flames in the kitchen you can be sure the stove's on fire.

On the CNN news website, I entered the same neutral search term for the same time period (sorted from newest to oldest). This time, only 2 of the first 12 hits, and none of the next 6, concerned increasing crime rates. The stories mostly concerned specific crime incidents.

This is a simple (obviously limited) demonstration that Republicans are fed a steady diet of crime-related news that doesn't just convey specific incidents but explicitly mentions a sharp increase in crime, usually in the headlines. This is fake news.

As for Democrats, the fact that just over half seem to believe that crime is increasing may simply reflect the salience of this particular phenomenon. Over and over we hear about the latest crime, we learn the gory details, and many of us have either been victimized ourselves recently or know someone who has been. Naturally, our gut tells us that crime is increasing. I wouldn't expect (or want) anyone to keep a running tab of how many crimes they heard about each month.

Let me put it this way: Because crime is so salient, when it increases, we should expect very few people to incorrectly perceive that it's declining. When it actually does decline, we can expect many more people to incorrectly report an increase. So, my speculation is not that Fox News and other conservative media are wholly responsible for the near consensus among Republicans that crime is increasing, but rather that Fox et al. are exacerbating a natural tendency.